Pride, Prejudice, and Population

By Cassidy Warner

Staff Writer

31/3/2022

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a nation with low birth rates and a rapidly-aging population must be in want of immigrants. Japan, however, is shutting its eyes to this truth. Despite having one of the fastest-aging populations in the world, it stubbornly refuses to replenish its workforce by promoting immigration. Proud and insular, Japan is like an old aristocratic family, clinging to its traditions and resisting the infusion of new blood into its ranks; it resembles the snobby Mr Darcy in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, who initially spurns the protagonist, Elizabeth, because of her low birth. Only, Japan doesn’t have Mr Darcy’s £10,000 a year, arguably his most attractive feature.

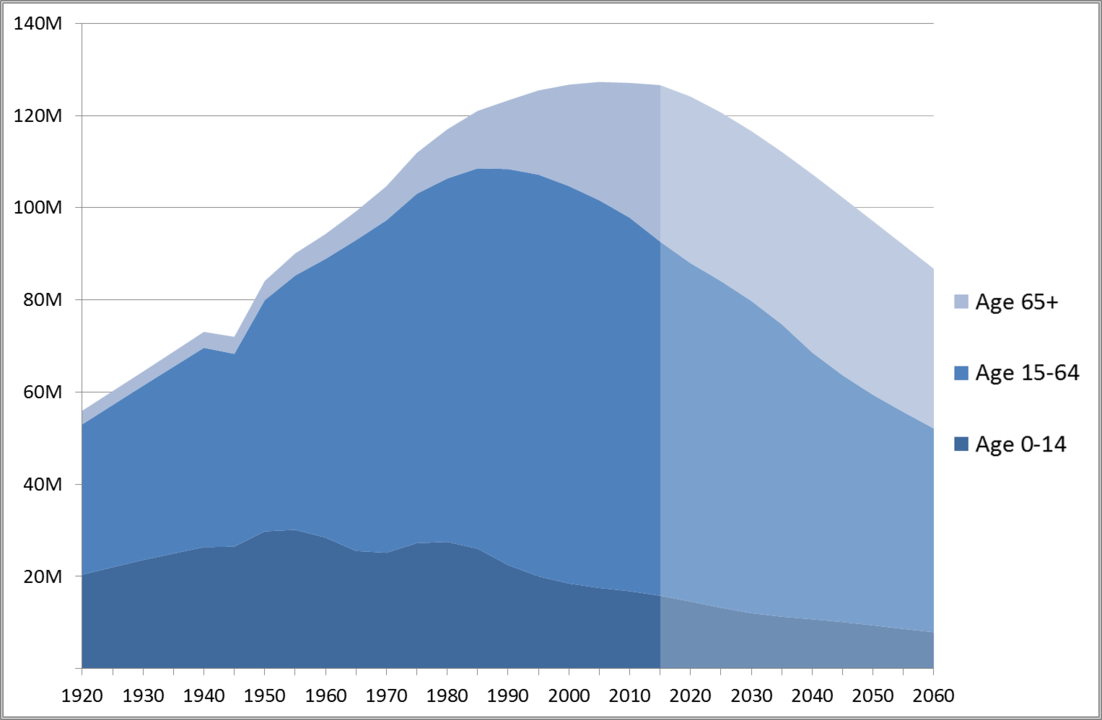

Japan’s population problem is often attributed to its low birth rate, but this is a misdiagnosis. Japan does have an alarmingly low birth rate, but, in truth, it is its death rate that is too low. Japan has the highest life expectancy in the world (currently 84.7 years, and projected to increase to 91.6 by 2050), and this puts enormous stress on the economy and the relatively small working-age population that is needed to support the retirees. In 2020, over 28% of the Japanese population was older than 65 (the retirement age), and that percentage is estimated to increase to around 40% by 2050. Japan has also been slow to abolish mandatory retirement ages and to raise the age at which old-age pensions can be accessed, pushing older, but still productive, workers out of the workforce, often before they want to retire. Theoretically, this opens space for younger workers to get jobs and promotions, but it also worsens the ratio of the working to non-working population.

Japan’s demographics from 1920-2010, projected to 2060, from the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (Picture Credit: JonMcDonald)

This problem is most glaring in rural Japan. In 1950, 53.4% of Japanese people lived in the countryside, but by 2015, that percentage had dropped to just 8.2% as young people left their hometowns to pursue opportunities in the cities. In rural areas, the percentage of people aged over 65 is already 37%. According to a report from the Japanese Ministry of Internal Affairs, more than 22% of Japanese towns have populations that are predominantly over 65, and 280 towns had nobody younger than 75 at all. Japan’s farming sector is particularly affected by this, as 60% of farm workers are 65+ and the average age is 67. With few (or no) working-aged people in these rural towns to drive their economies and to support and care for the seniors, businesses and farms wither away and local communities are left floundering.

Japanese rice farmer

The logical solution to this problem would be to actively increase Japan’s working-age population by any means necessary, especially in rural areas. The Japanese government’s efforts, however, have been anemic.

Take, for example, Japan’s empty houses, called “akiya.” In 2021, Japan’s property vacancy rate was 14%, increasing to 16% in rural areas; some prefectures even had vacancy rates higher than 18%. Local governments have tried to refill these abandoned properties by reducing taxes on them, offering grants for renovation, sometimes even giving them away for free. But these policies have been largely unsuccessful because, ultimately, they are aimed at the wrong audience. Japan is attempting to reverse rural-to-urban migration, but people already living in cities expect city amenities and white-collar jobs that rural towns, lacking convenience stores and high-speed internet connections, do not have.

The people who would truly be interested in living in the Japanese countryside are immigrants with similar, but less affluent lifestyles elsewhere, or carers specifically imported to cater to the aging populations in the area. However, Japanese property owners are reluctant to sell or rent to foreigners (one survey put this reluctance at 60%) and frequently racially discriminate against them when doing so. Japanese visas usually forbid workers from bringing their spouses or children to discourage them from settling permanently. Or, in rare cases where families are allowed to join workers, restrictions are placed on the spouses’ working hours that can make starting and supporting a family difficult or impossible. Even if immigrants can run this gauntlet of unfavorable policies, they still find it hard to be accepted by Japanese society. Richard Koo, chief economist at Japan’s Nomura Research Institute, said that rural towns have “an exclusionary attitude” and a “very, very closed society” that can take decades to accept outsiders.

Eiji Oguma, an historian and sociologist at Keio University, explained that Japan’s immigration policies are aimed at “sustaining” Japanese society, not changing or expanding it. In other words, Japan has no interest in using non-Japanese people to solve its population problems, only in using them as band-aids over the leakiest wounds. Thus, Japan’s immigration policies are begrudging, and it tolerates behavior that makes Japan unappealing to foreigners.

Japan’s immigration policies are begrudging, and it tolerates behavior that makes Japan unappealing to foreigners.

As a result, Japan’s immigration policies fail to meet its needs. For example, a 2019 immigration policy designed to bring in 5,750 workers per month only attracted around 3,000 before COVID sealed the borders. More recently, Japan relaxed immigration policies for care workers, allowing them to stay on indefinitely under certain conditions. But 16-38% of eligible migrants chose to go home because of Japan’s unreasonable, even exploitative, working conditions. Foreign workers regularly complain of abusive practices and are twice as likely to die in work-related accidents as their Japanese counterparts, mostly due to exploitative or unsafe conditions that are more common in the trainee roles held by immigrants.

The reality is that Japan is one of the least-desirable destinations in the developed world for immigrants, coming only 24th amongst OECD countries. Japan’s net migration rate has been in decline since 2018, meaning that fewer people are arriving in Japan each year than the year before, despite the fact that immigration policies have been steadily relaxing. In 2022, Japan is expected to net only 0.525 immigrants per 1,000 people, compared to 6.18 in Canada, 5.42 in Australia, 4.57 in Singapore, 3.32 in Hong Kong, and 2.70 in both the US and New Zealand.

Japan’s low migration rate is a perfect illustration of Japan’s superiority complex at work; because it is incomprehensible to the Japanese that inferior people would not jump at the chance to live in Japan, even temporarily under unfavorable, unwelcoming conditions, the government doesn’t even try to attract them.

The government takes the same supercilious attitude towards dual citizens, particularly people from dual-nationality households, who are expected to choose only one nationality by their 22nd birthday. Japan does not recognize dual citizenship; applicants for Japanese citizenship must forfeit their original citizenship and Japanese citizens cannot acquire citizenship anywhere else without forfeiting their Japanese one. Forfeiting Japanese citizenship means giving up the right to live and work in Japan without restrictions and becoming subject to the same visa requirements as every other foreigner. Those who do then need to wait a minimum of a year – but more likely 3-10 – before jumping through a series of residential and financial hoops to be eligible to apply for permanent residency. Obviously, Japan expects people to choose Japanese citizenship, but for those who are half-Japanese, the choice is not so clear. One young woman likened the experience to being asked to “choose whether they love their mother or father more.” Another man, Hitoshi Nogawa, who was forced to give up his Japanese citizenship to work in the EU, (unsuccessfully) sued the Japanese government for emotional damages, calling the decision process a “painful experience.”

For others, though, their experiences with Japanese attitudes have made the choice easy. A young woman spoke to me about being thoroughly put off by the citizenship ultimatum and, combined with her experiences of racially-motivated bullying and exclusion growing up in Japan, was only too happy to choose her alternate citizenship. Similar online discussions between Japanese of mixed descent often relate similar experiences of casual racism and complain that Japanese people view half-Japanese as inferior or other. One person said that they had “given up waiting” to be accepted and that they were “better off just forgetting it.” Another person of mixed blood was straight up told by a teacher, “you are not Japanese.” One woman catalogued her experiences of racism, confessed that her partner was half-Korean (“shock horror!”), and said that they were “planning their escape.” Another commenter agreed, saying, “if I ever have kids here I’m taking my family and [moving] back to the states ASAP.”

In all the ways that matter, Japan has allowed its insularity and superiority complex to sabotage its future. The solutions to some of these issues seem obvious: attracting immigrants would help solve Japan’s demographic crisis; encouraging property owners to sell and rent to foreigners would help fill those empty homes; and recognizing dual citizenship would encourage those of mixed heritage to remain in Japan instead of leaving.

Japan has allowed its insularity and superiority complex to sabotage its future.

Only some sections of Japanese society seem to recognize how badly the country needs immigrants. Only 1 in 10 workers in Japan’s construction industry are under the age of 29, and 1 in 3 are over 55. So for people like Yasutake Maeda, the owner of a construction company, immigrants are “indispensable,” and he even prefers them to young Japanese workers because they are “more hardworking.” Masayoshi Tabata, general manager of Shigeru, a car parts manufacturer, also regards foreign trainees as more “dependable” than Japanese ones. And for Kota Hirohara, a cabbage farmer, immigrant workers are the only thing keeping him in business, as younger Japanese won’t consider working on his farm at all.

Colin Firth as Mr Darcy and Jennifer Ehle as Elizabeth in the 1995 Pride and Prejudice series

But tolerating immigrants is only the first step. Let us not forget Mr Darcy’s terrible blunder: “She is tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me,” he said of Elizabeth, within her hearing. Tolerance is not enough; if Japan hopes to attract immigrants, heartfelt courtship is required. If Japan cannot let go of its pride and prejudice, if it cannot cultivate a little humility, it should not be surprised when immigrants continue to scorn its reluctantly-made, insultingly-phrased proposals. Until then, Japan’s demographic crisis will continue to worsen, and the country will remain unable to produce the heirs it so desperately needs.