The Canada I Know

By Steve Noyes

Contributor

17/11/2019

In early 2017, Charles Foran, the well-known Canadian novelist and biographer, suggested in The Guardian that Canada is a post-national nation, welcoming to immigrants, celebrating diversity through an official policy of multiculturalism, and able to exist without a firm nationalist identity. Foran noted that Barack Obama and Bono had both declared that “the world needs more Canada,” and that on the eve of Donald Trump’s election in the United States, Canada’s official immigration website crashed due to heavy traffic.

Canada, Foran wrote, could serve as model for other countries: “If the pundits are right that the world needs more Canada, it is only because Canada has had the history, philosophy and possibly the physical space to do some of that necessary thinking about how to build societies differently. Call it post-nationalism, or just a new model of belonging: Canada may yet be of help in what is guaranteed to be the difficult year to come.”

Foran was articulating a view that many Canadians – and others – have of the country: tolerant, peaceful, not given to patriotic fervor. He is not entirely wrong. Since the 1970s, the Canadian government has promoted a policy of multiculturalism, defining Canada as a place welcoming to all and accepting – even celebrating – difference. Some American travellers stitched Canadian flags to their backpacks, hoping to avoid their own country’s unpopularity abroad by donning a Canadian disguise. Canada’s citizens enjoy universal free health care at the point of service, which was often cited during the American debates over Obamacare. When the Canadian military went abroad, it was usually as United Nations peacekeepers or to aid disaster relief efforts.

The Canadian government has promoted a policy of multiculturalism, defining Canada as a place welcoming to all.

Justin Trudeau’s first election as Prime Minister in 2015 seemed to solidify Canada’s status as a progressive, multicultural country, as Trudeau promised to do politics differently. On election night, he said “We know in our bones that Canada was built by people from all corners of the world, who worship every faith, who belong to every culture, who speak every language.” Photogenic, eco-feminist, internationally famous, he deliberately appointed a cabinet that was 50% female, and welcomed 25,000 Syrian refugees into Canada.

Justin Trudeau at a gay pride parade in Toronto in 2015 (Picture Credit: Alex Guibord)

In his re-election campaign last October, in Mississauga, Ontario, though, Trudeau appeared at a campaign rally in a bulletproof vest, with several security personnel surrounding him, because of a threat.

Assassination threats? In Canada? That peaceful land of hockey-moms, toque-wearing singers performing in sub-zero football stadiums, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police? Really?

Responding to this story on Facebook, Canadians chimed in with a common refrain: “This is not the Canada I know,” and its various iterations:

This is NOT the Canada I know!

This is Canada, how can this be happening?

I just hope that this beautiful and safe country of ours doesn’t adopt the american (sic) way of doing politics.

The last comment reflects the common Canadian belief that Canada cannot possibly be as divisive, angry, or dangerous as the United States, but it struck me at best as a form of magical thinking, a shifting of responsibility.

The last comment reflects the common Canadian belief that Canada cannot possibly be as divisive, angry, or dangerous as the United States.

Canadian political leaders do get threatened. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) reported in May 2018 that, according to “security occurrence reports” complied by Alberta Justice, former Alberta Premier Rachel Notley had received 11 death threats over three years. The CBC reported that female Members of Parliament have installed panic buttons and hired more security personnel as online threats against them have escalated.

Trudeau survived the election, literally and figuratively, but with a minority government sharply reduced in power, with no representation in Alberta and Saskatchewan, two western provinces, whose political leaders are now making public statements, however unrealistic, about separating from Canada. He also suffered significant losses in Quebec, to the Bloc Quebecois Party, who supported Quebec’s controversial legislation, Bill 21. The law prohibits the wearing of religious symbols and clothing for those in public office, which contradicts Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms’ ban on religious discrimination. Trudeau was the only national party leader to say that, if elected, he might send federal lawyers to the Supreme Court to argue against the Bill.

Quebec City

Trudeau must now govern a country showing the same signs of intolerance, divisiveness, and violence as other countries. Toronto, for example, faces similar levels of gun crime and hate crime as cities in the United States.

It would be easy to assume that Canada must have a better record on gun crime than America. Canada has restrictive gun laws – citizens must register their guns, and carry them unloaded in the trunks of their cars – compared to America, where in many states people can openly carry guns. According to the Toronto Police, Toronto’s shootings increased over the past 10 years from 238 to 428, an increase of 57%. Comparing Toronto’s 2017 shootings with Chicago’s, a city about the same size on the other side of the Great Lakes, Toronto had 2,032 shootings, while Chicago had 2,782 shootings. In other words, Toronto had 73% of the Chicago total, arguably in the same league.

Statistics Canada’s report on firearm-related violent crime, found that the rate of gun-related violent crime in Toronto doubled from 18 per 100, 000 to 36 per 100,000 from 2013 to 2017, while the overall Canadian rate rose from 19 to 27 per 100,000 over the same period, an increase of 42%.

Toronto

Hate crimes are also increasing in Canada. Statistics Canada reports that reported hate crimes in Canada climbed from 1,295 to 2,073 from 2014 to 2017, a 137% increase. In 2018, there were more almost twice as many hate crimes in Canada (2,073) than in California (1,066), whose population is similar to Canada’s. A more precise comparison is with the 30 largest American cities, whose combined population is within 1 million of the total population of all Canada’s cities. According to Statistics Canada, the rate of Canadian hate crimes in cities is 5.9 per 100,000. A report by the Centre for the Study of Hate and Extremism at the University of California at San Bernardino, drawing on statistics from those 30 largest American cities, put the American rate at 5.2 per 100,000.

Dr Barbara Perry and Dr Ryan Scrivens published a survey of Canadian right-wing extremist hate groups in 2015, when they found that there were approximately 100 hate groups operating in Canada, about one-tenth of the 1,020 American hate groups documented in 2019 by the Southern Poverty Law Centre – exactly proportional for a country with a population one-tenth that of the States.

White supremacist demonstrators in Calgary

In an email, Dr Perry said, “I, myself, have been guilty of exclaiming that this is ‘not my Canada,’ knowing full well that we are a white settler nation with a long history of popular and systemic forms of othering. But there is something different about the depth and breadth of hate that we are seeing in so many diverse forms: hate crime, hate speech, the growth of organized hate groups, and the normalization of hate that informs all of these.”

Dr Poole believes that hate crimes and displays of racism are directly associated with the election of Donald Trump, and more specifically, his deliberate populist appeal to white Americans who feel threatened and victimized by the liberal elite and by immigrants they consider to be “other.” In “The Danger of Porous Borders: The Trump Effect in Canada,” Dr Perry documented a definite spike in hate incidents following Trump’s election victory in 2016:

“In Ottawa, Canada’s capital city, visible minority communities were the targets of several hate-inspired incidents following Trump’s victory, which began on November 13th and lasted until November 19th; two synagogues, a Jewish prayer house, a mosque, and a church with a Black minister were vandalized with spray-painted racial slurs, swastikas, and white supremacy symbols. Other Canadian cities (Toronto, Richmond, Regina) experienced a similar uptake in targeted hatred.”

The increase in racism is not confined to a narrow subset of the population. A national IPSOS poll in 2018 found that almost half of Canadians (47%) will admit to having racist thoughts, and more feel comfortable expressing them today than in years past.

Dr Rima Wilkes studies racism at the University of British Columbia. She thinks the “Not my Canada” reaction is a self-congratulatory displacement common to many countries. “I think the issue is that most people want to believe that they and their nation are one of the ‘good’ ones,” she said, “so Canadians tell themselves that they are good because we don’t have that awful history of slavery that the US does and therefore that racism never was or isn’t a problem here (false); Americans tell themselves that they are good because they are not the Germans (and now they can’t understand why there is this resurgent anti-Semitism) and I’m sure every country in the world does this. We always want to locate racism/genocide (which all of us know is bad) somewhere else.”

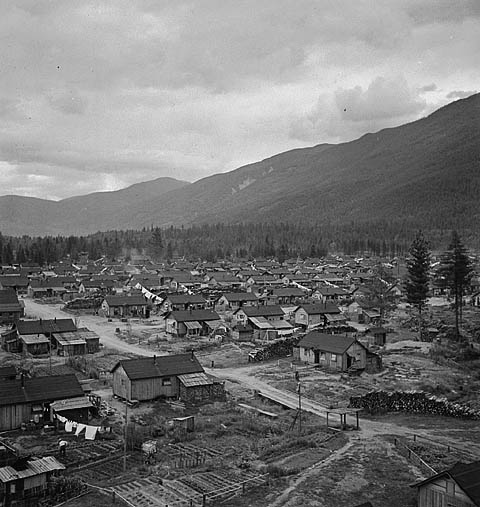

But Canada has a long history of treating people who seem different, well, differently, especially in wartime. From 1914 to 1920, Canada rounded up more than 8,000 Ukrainian-Canadians and placed them in camps; in 1942, again, Canada placed more than 8,000 Japanese-Canadians in camps and took away their property; Canada also forced more than 80,000 Chinese immigrants from 1885 to 1923 to pay a substantial head tax (as much as $500) not levied on any other immigrants during the period.

Internment camp for Japanese-Canadians in 1944

Even more egregiously, Canada has arguably had its own state-sponsored genocide, perpetrated upon the aboriginal peoples, or First Nations, as they are now called.

The government of Canada passed the Indian Act in 1876, According to The Canadian Encyclopedia, “The Act was an attempt to generalize a vast and varied population of people and assimilate them into non-Indigenous society, and therefore forbade First Nations peoples and communities from expressing their identities through governance and culture.”

Over the years, this policy of forced assimilation was strengthened by amendments to the Act: to require First Nations children to attend industrial or residential schools (1894 and 1920); to prohibit the practice of religions ceremonies like the potlatch (1884); to prohibit Indian dancing ceremonies (1925); to make it illegal for First Nations communities to hire lawyers or make land claims against the government without official consent (1927).

The Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued its final report on the residential school system in 2014, after six years of public events and gathering over 6,000 statements from victims, family members, school administrators, government officials, social workers, and the police. The report said: “these children were sent to what were, in most cases, badly constructed, poorly maintained, overcrowded, unsanitary fire traps. Many children were fed a substandard diet and given a substandard education, and worked too hard. For far too long, they died in tragically high numbers. Discipline was harsh and unregulated; abuse was rife and unreported. It was, at best, institutionalized child neglect.”

The report concluded: “That policy was dedicated to eliminating Aboriginal peoples as distinct political and cultural entities and must be described for what it was: a policy of cultural genocide.”

Canadian residential school

After the report was published, then Prime Minister Stephen Harper made a formal apology, in which he acknowledged that the primary objectives of the policy were “based on the assumption Aboriginal cultures and spiritual beliefs were inferior and unequal. Indeed, some sought, as it was infamously said, ‘to kill the Indian in the child.’ Today, we recognize that this policy of assimilation was wrong, has caused great harm, and has no place in our country.”

Canada’s lack of a “firm nationalist identity,” noted by Charles Foran at the beginning of this article, now seems to us like a space in which markedly different notions of Canadian identity contend. As the novelist Arundhati Roy suggested, the issue of identity is a battle of props and costumes. It is mostly symbolic, emotional, and illogical, as a couple of recent incidents illustrate. Take this election exchange between National Democratic Party Leader Jagmeet Singh, who is a Canadian Sikh, and a white Canadian:

“You should cut your turban off,” said the man. “You’ll look like a Canadian.”

Singh responded, “I think Canadians look like all sorts of people. That’s the beauty of Canada.”

What does a Canadian look like? What does a Canadian wear? Backwards baseball caps? Montreal Canadiens jerseys? Burqas? Aboriginal jingle-dresses?

One might well say, “So what?” – Singh was confronted by a lone crank in a parking lot.” Well, how about a crank that enjoyed a weekly television audience of more than 2 million? On the eve of Remembrance Day, a Canadian icon, the ice-hockey commentator Don Cherry, berated immigrants on air for not wearing poppies to remember fallen Canadian soldiers.

“You people…you love our way of life, you love our milk and honey, at least you can pay a couple bucks for a poppy…These guys paid for your way of life that you enjoy in Canada, these guys paid the biggest price.” (Cherry was fired for the remarks.)

Don Cherry at the 2002 Winter Olympics at Salt Lake City

If Canada is such a paradise, a land of “milk and honey,” whose is it? Who are the “we” implied in “our,” and who are “you people?” How on earth could Cherry tell the difference?

What is a Canadian? Recent immigrant, historical immigrant, First Nation, settler, a Canadian is someone who holds Canadian citizenship, a simple concept that, unfortunately, some Canadians cannot grasp.