The Culture Factor in COVID-19

By Michael Pusic

Staff Writer

13/5/2020

In October 2019, just months before the coronavirus upended the world, a group of top experts in epidemiology published a report ranking 195 nations based on how prepared they were for a pandemic. The main authors were esteemed professors of public health at Johns Hopkins University, funded generously by the Gates Foundation, The Economist, and several other large institutions. The Global Health Security Index (GHS), as it’s called, took into account quantitative metrics of countries’ ability to prevent, detect, and respond to the emergence of a pathogen, as well as their general political, economic, and healthcare attributes.

The report concluded that the most prepared nation for a pandemic was the United States. The second most prepared was the United Kingdom.

As of May 4th, 2020, the United States has the most COVID-19 cases in the world, and the United Kingdom has the second most deaths. Meanwhile Iraq, which the GHS ranked 167th out of the 195 countries examined, has had just 104 deaths.

That a panel of the world’s foremost experts, provided with full funding, could not predict which countries would suffer most from a pandemic speaks to how difficult it is to discern why some nations have been devastated by the virus, while others have escaped largely unscathed. As researchers scramble to find an answer, explanations seem to dissipate as quickly as they appear.

One theory is that the lower the average age in a country is, the fewer deaths it’s likely to have. Italy, for example, has one of the highest average ages and one of the highest mortality rates from the coronavirus at 13%. But Japan, where the average age is even higher, has a mortality rate of just 1.6%.

Another is that the virus spreads more quickly in colder climates. This might explain why 75% of Italy’s cases are in its northern regions. But experts, including Marc Lipsitch at Harvard University and Dr Raul Rabadan at Columbia University, are starting to doubt this theory, suggesting that the role of climate is likely negligible compared to other factors.

Of course, the speed and severity of a nation’s response to COVID-19 plays a large role in determining the number of infections and casualties. Researchers at Oxford ranked the stringency with which countries responded to the COVID-19 outbreak and found that those who instituted more measures earlier on saw significant reductions in the spread. African nations that have faced public health crises like this before — like Senegal, Rwanda, and Uganda — closed their borders and began contact tracing while they still had relatively few cases, and seem to have stemmed the flow. But even this explanation remains incomplete, since just as many countries with just as few cases instituted few social distancing measures.

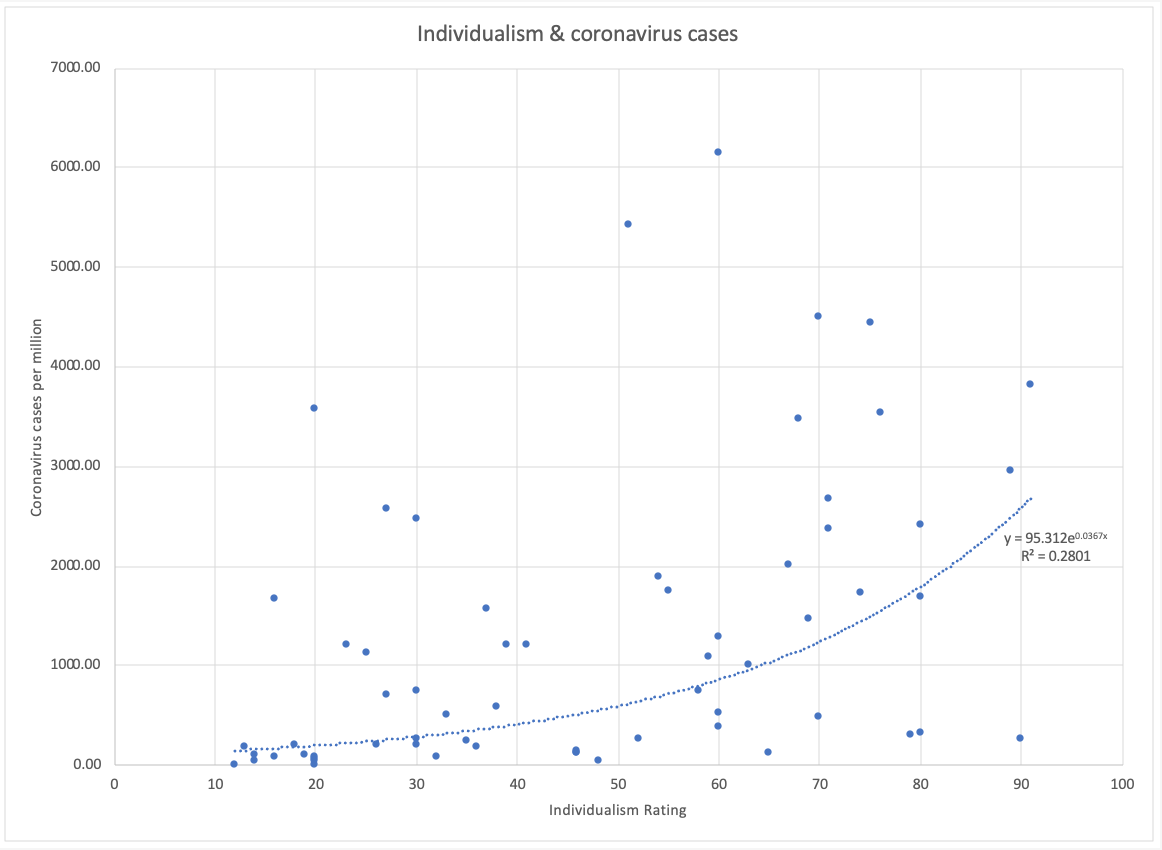

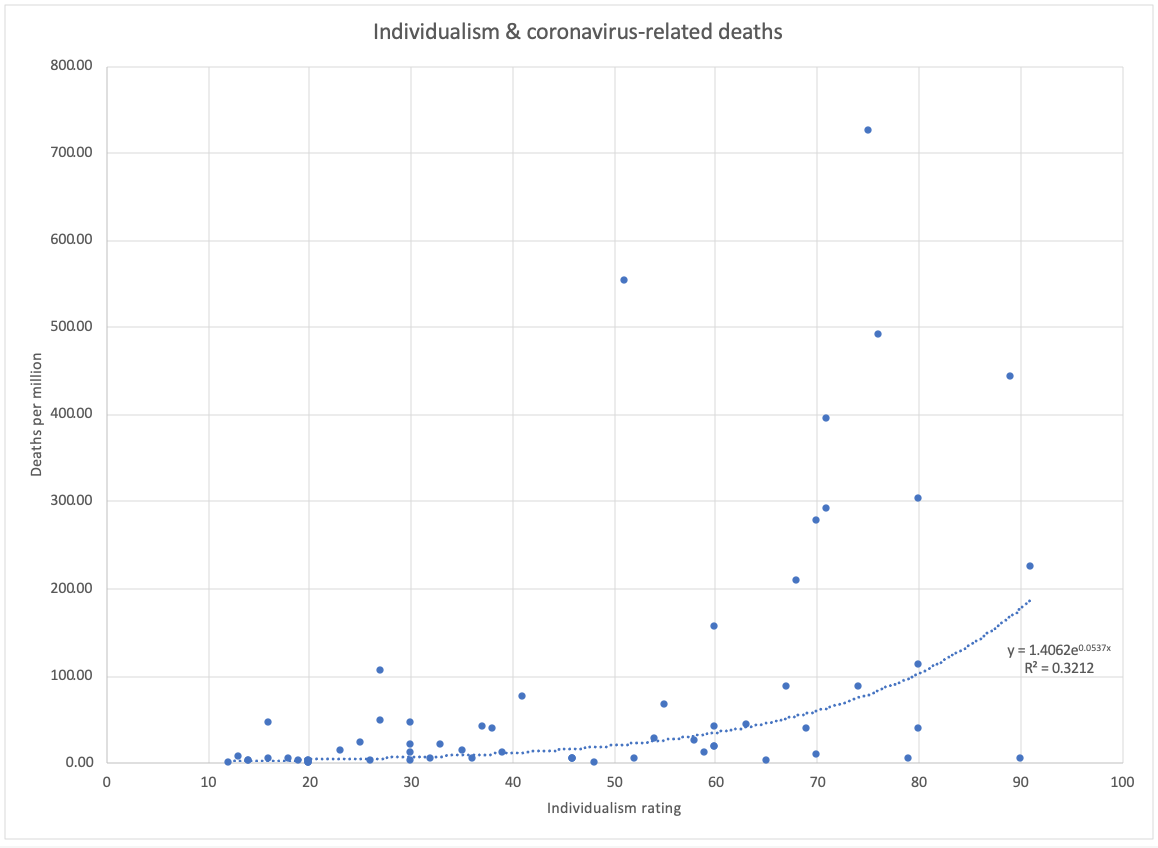

One factor that likely plays a significant role is culture, though it’s less commonly discussed. Since the spread of the virus in a country depends on the actions of the people there, its culture becomes an important piece of the puzzle. The logic of this is relatively intuitive: more individualistic nations like the United States are less likely to adhere to communitarian social distancing measures than, say, former Soviet-bloc countries. Italians, who greet each other with a series of kisses, are more likely to spread the virus than Japanese, who bow. But culture is an exceptionally hard thing to meaningfully describe, much less measure, quantify, and study in relation to a pandemic. As a result, nearly all commentary on the relationship between culture and COVID-19 to date has been anecdotal.

In the early 1980s, however, the Dutch psychologist Geert Hofstede published Culture’s Consequences, a seminal work which argued that from a young age we are culturally “coded” with certain social values and patterns of thought. He defined culture as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others.” Though not determinative, a culture makes it more likely that the people immersed in it will behave a certain way.

Though not determinative, a culture makes it more likely that the people immersed in it will behave a certain way.

Hofstede separated this collective programming into six dimensions across which culture could be quantified: individualist versus collectivist, equal versus unequal, masculine versus feminine, uncertainty avoidant versus acceptant, long-term versus short-term orientation, and indulgent versus restrained. Using hundreds of thousands of individual surveys that covered 99 countries and 85% of the global population, Hofstede and his researchers scored nations from 0-120 for each of these dimensions. These scores have been used in everything from economics to epidemiology to measure the social differences between countries.

To try to figure out how culture might affect COVID-19, I performed regression analysis, a method for investigating the relationship between variables, in this case, culture and COVID-19 infections and deaths. Because a country’s infection and mortality rates from COVID-19 are probably affected by a number of factors including its population density, GDP per capita, citizens’ average savings, national poverty rate, health expenditure as a percentage of GDP, average life expectancy, as well as the share of its population over age 65, the amount of testing it’s carried out to date, and whether it experienced a SARS outbreak in the early 2000s, I controlled for them in the regression. (You control for things in regressions by accounting for their effects in your model, such that those effects can be separated from the results your model yields.) My model produced equations describing the relationship between scores in the different cultural dimensions and COVID-19 infections and deaths.

My final dataset included over 2,700 data points across nearly a hundred nations, and my regressions were all robust against a number of routine statistical checks (e.g. collinearity, heteroscedasticity, independence of observations, normality in error distribution, influence from outliers, and model specification). It’s crucial to note, however, that this is preliminary research; these findings are not final or in any way impervious to further inquiry. Academic articles are likely to appear on questions like this months from now, with far greater statistical rigor.

Figurines in Singapore’s Chinatown (Picture Credit: cattan2011)

The main finding was a clear link between culture and COVID-19 infections and deaths. When I attempted to predict countries’ number of infections per million using all the control variables listed above, but none of the cultural factors, the resulting regressions explained slightly less than half of the variability in countries’ infection rates. When I added in Hofstede’s cultural scores, the regressions predicted 94% of the variability in countries’ infection rates. When I repeated this process for the number of deaths per million, there was a 70% jump in the amount of variance explained; and for the mortality rate, there was a 29% jump. To be sure, the data only shows that culture correlates with COVID-19 infections and deaths, not that it causes it. It is, however, reasonable to theorize causation from these results, and to say that culture may be an important determinant of COVID-19 infections and deaths above and beyond what would be predicted by most conventionally considered factors like demographics, quality of healthcare, and economic well-being.

More specifically, I found that across almost all regressions, countries that were more individualistic, indulgent, and that had lower uncertainty avoidance had higher numbers of cases and higher mortality rates.

countries that were more individualistic, indulgent, and that had lower uncertainty avoidance had higher numbers of cases and higher mortality rates.

The Hofstede Institute defines individualism as “the extent to which people feel independent, as opposed to being interdependent as members of larger wholes.” A higher score on the individualism rating indicates that members of the society are more independent, while a lower score suggests a more communitarian outlook. In my analysis, a country being one point more individualistic (that is, one point higher on the 0-120 scale) was associated with an increase of 15 cases per million and a .107% increase in mortality rate. It could be that countries with higher scores are more likely to value individual freedom over communal security, and so are more reluctant to follow stringent social distancing measures.

Hofstede wrote that the difference between indulgent and restrained cultures is in how they articulate the good life. In indulgent cultures the good life is defined by freedom, “doing what your impulses want you to do, is good”; in restrained cultures, “the feeling is that life is hard, and duty, not freedom, is the normal state of being.” Accordingly, a higher score on the indulgence rating indicates a potentially more impulsive society, and an increase by one point corresponds to a .058% increase in mortality rates, and 4 more cases per million.

Finally, a nation’s uncertainty avoidance rating naturally indicates a society’s aversion to ambiguity. A country with a relatively high score for uncertainty avoidance is less likely to implement policies or take actions that have large unknowns. Inversely, some have linked the United Kingdom’s initial herd immunity policy to its low score for uncertainty avoidance. In my analysis, I found that a one point decrease in a country’s uncertainty avoidance score was associated with a .3% increase in its mortality rate, and an increase of 18 cases per million overall. This finding is in agreement with the general consensus that more risk-averse countries which implemented more stringent lockdowns earlier on have suffered less.

Bringing these factors together, countries with a single point above average in their individualism and indulgence ratings, as well as a single point below average in their uncertainty avoidance ratings, could suffer significantly more from the pandemic. Though it’s not as simple as just adding these numbers up to calculate their cumulative impact, you get a sense of the significance of these cultural differences if you consider that if the US were one point more averse to uncertainty, it might have had nearly 6,000 fewer cases, and 3,870 fewer deaths (uncertainty aversion affects cases and mortality rates to different degrees).

If the US were one point more averse to uncertainty, it might have had nearly 6,000 fewer cases, and 3,870 fewer deaths.

Though these findings may seem intuitive, they may provide the beginnings of an answer to many questions. For example, they could partially explain why the United States and United Kingdom, despite being ranked as the most prepared countries for a pandemic by the Global Health Security Index, have suffered so badly. Both are among the most individualistic nations in the world, with ratings of 91 and 89 respectively out of 120; both are also particularly high in indulgence (they score 68 and 69 respectively, while the median is just 46), and low in uncertainty avoidance (46 and 35, where the median is 68). Thus, while these countries may have had the technical capacity to respond to a pandemic, their cultures were particularly ill-suited to an outbreak — people there are less willing to control their desires, less willing to trade individual freedom for communal security, and more willing to accept the ambiguity caused by high-risk actions.

American anti-lockdown protestors at the Ohio Statehouse, 20th April 2020

These factors may also explain why some countries that were technically less prepared for a pandemic have fared better than expected. For example, Pakistan and Bangladesh, which were ranked 105th and 113th out of 195 nations by the Global Health Security Index, have only had 109 and 75 cases per million respectively, and fewer than 3 deaths per million collectively. Pakistan and Bangladesh are amongst the most restrained, collectivist, and uncertainty avoidant countries in the world. To cite an even more extreme example, Iraq, which was ranked as one of the 30 least prepared countries in the world by the GHS, has had just 104 deaths in total since the outbreak began. Perhaps not coincidentally, it’s also one of the most collectivist, restrained, and uncertainty avoidant countries; scoring just 30 on individualism, 17 on indulgence, and 85 on uncertainty avoidance.

The real test of this theory, however, will not be how well it fits with existing cases, but how well it predicts future outbreaks. Australia and New Zealand may face high risks of re-infection as their lockdowns ease, given that they’re both in the top 10% of countries for individualism and indulgence. Additionally, despite early reports to the contrary, Sweden’s approach of dealing with the coronavirus without a lockdown may prove misguided given that it ranks highly across all three cultural risk factors. In each of these three countries, citizens will generally be less likely to take additional precautions against the virus without coercion by the state.

The real test of this theory will not be how well it fits with existing cases, but how well it predicts future outbreaks.

Meanwhile, low-risk cultures may slow the spread of the virus in certain nations. Though Russia is currently seeing a rapid increase in cases, its populace is relatively collectivist, extremely risk averse, and highly restrained, all of which may contribute to a lower plateau than is currently forecasted. Thailand also has a relatively low-risk cultural profile, with scores of 20 for individualism, 64 for uncertainty avoidance, and 45 for restraint. This may not only explain why its outbreak has been relatively moderate, but may also indicate that it’s likely to remain so. Finally, though South Korea’s case numbers are still increasing, the fact that it scores an 18 on individualism, an 85 on uncertainty avoidance, and just a 29 on indulgence, suggests they may peak sooner than expected, and thereafter decrease quickly.

Despite the evidence we’ve accumulated, it may simply be too soon to make educated guesses as to what cultural factors predict worse outbreaks, and which countries are likely to escape relatively unscathed. As researchers and as victims of the virus in some form or another, we can only plod through this pandemic as it unfolds. It may be that culture plays a significant role in the outbreak, but it may also be that other factors, like air pollution and genetics, play an even greater role.

But whatever effect culture may have on the coronavirus’ spread, the virus will certainly affect our various cultures in many ways. Slavoj Žizek has predicted the renewed appreciation for big government and human solidarity will lead to a resurgence of communism. But even short of a people’s revolution, Italians might become more restrained (not least in their greetings) and more communitarian, and typically uncertainty accepting nations like Indonesia may become more risk-averse.

What effect these cultural changes will have is too big a question for any data analysis, but it’s an important one. COVID-19 has already transformed our daily lives, but the most enduring changes will be to our values, to our collective identity. This subterranean cultural shift currently at work will only become apparent long after the virus has passed.

Related posts:

Your Odds of Dying From COVID-19 Depend on How Polluted Your Air Is

Japanese Culture Isn’t Designed to Handle a Pandemic

The Moral Foundations of Anti-Lockdown Anger

Are Anti-Lockdown Protests Legal?

Tablighi Superspreaders in Pakistan

Modi and His Supporters Face a COVID Reckoning

Allegory in the Time of Coronavirus

The Coronavirus and the Crisis of Responsibility

To See How Coronavirus Outbreak might Play Out, Look at This Virtual Plague

FAKE NEWS | Nothing to Worry About, Says Wuhan Official From Inside Biohazard Suit