The Parasite and the Awards Host

By Lisa Yin Zhang

Staff Writer

2/3/2020

In Parasite, everything is twisted: down is up and up is down, at least until the whole edifice collapses. The same parasitic inversion of power seems to extend even to its making: Bong Joon Ho, the newly universally-beloved multi-Oscar-winning director of Parasite, recently recalled an encounter with Harvey Weinstein, the former movie mogul, now convicted rapist. Working on Snowpiercer (2013), Weinstein had insisted on cutting a scene, in which a character guts a fish. “Harvey hated it,” said Bong. “I said, ‘Harvey, this shot means something to me. My father was a fisherman. I’m dedicating this shot to my father.’” Weinstein, allegedly, was moved. Family, he told Bong, is the single most important thing to him. He let him keep the shot. “It was a fucking lie,” Bong said. “My father was not a fisherman.”

In deceiving a foolishly trusting host, consuming its resources (and bonus: coming back around to gloat), Bong is not unlike the protagonists of Parasite. On recommendation from a wealthy friend, Ki-woo, young, bright, but diploma-less, becomes the English tutor of Da-hye, the teenage daughter of the wealthy Park family. The parasite latches, and his fellows soon follow: his sister, Ki-jung, becomes “Jessica,” the art therapist; his father, Ki-taek, the chauffeur; his mother, Chung-sook, the housekeeper. But is the Kim family really the parasite?

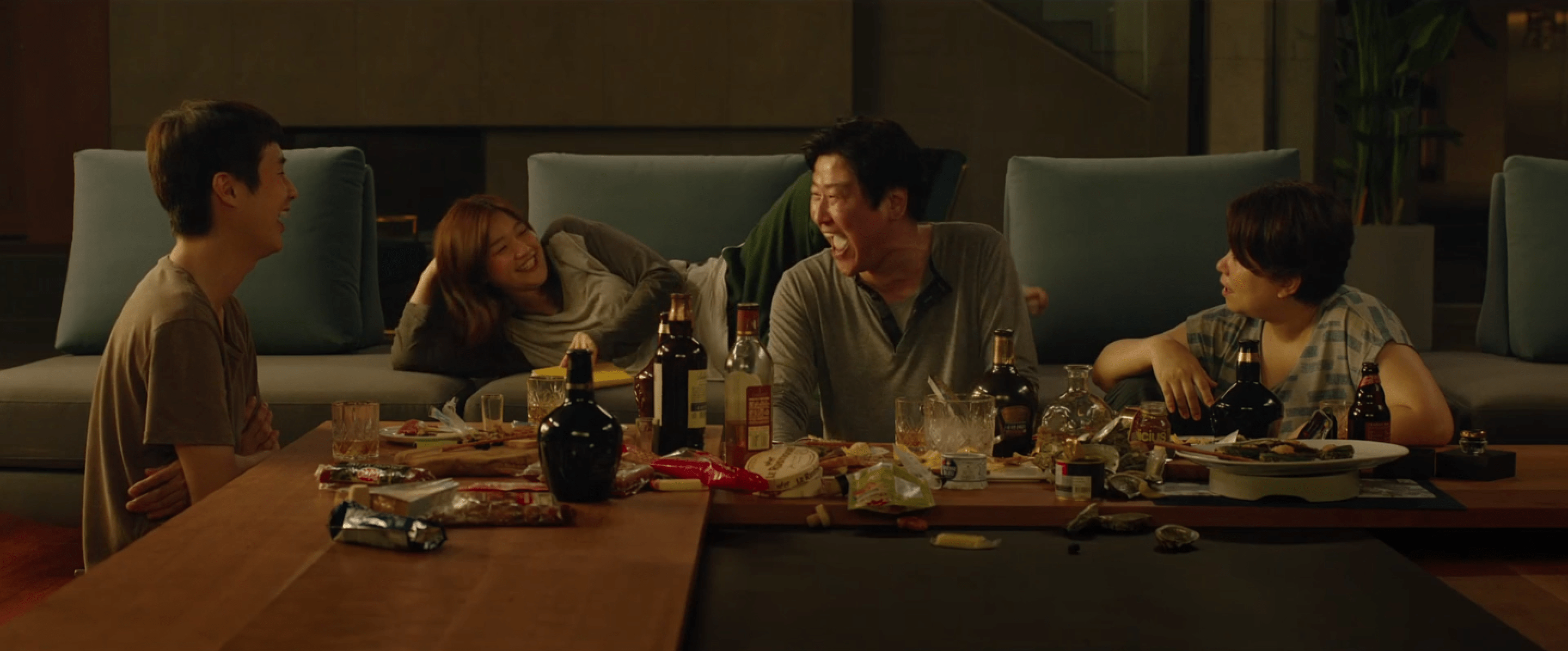

A parasite is an organism that lives off an organism of another species, deriving nutrients at its host’s expense. It comes from the Greek parasitos: para (beside, by), and sitos (wheat or food), meaning “one who eats at the table of another.” It’s hard not to watch the scene in which the Kims drunkenly lounge at the Park’s coffee table with a slovenly spread of snacks, charcuterie, and liquor, and not think them parasites. Ki-jung rises from a supine stupor only to curse loudly; Ki-taek shatters glass bottles across the floor; Chung-sook literally hits a dog. They’re disgusting, drunken, and gluttonous. But at this point in the film, at least, the parasitic Kims have not caused the host Parks any harm. In fact, they’ve been a great help: there are no complaints about the quality of Ki-woo’s tutoring, Ki-taek’s driving, Chung-sook’s cleaning. Is it so parasitic to want to labor for a living?

The Parks, on the other hand, are helpless without the labor of the Kims, relying on them to complete basic tasks for survival. “In a week, our house will be a trash can,” complains Dong-ik, the Parks’ patriarch, after the Kims-induced loss of his old housekeeper, Moon-gwang. “My wife has no talent for housework. She’s bad at cleaning, and her cooking’s awful.” It is, rather, the Kims who are resourceful — cleaning the house, making ram-don, arranging fancy parties, often based solely on information gleaned from the internet. If the Parks must also depend upon the Kims, then they, too, are parasites. Within Parasite, and in the discourse that now surrounds it, relations are muddled: which one is the parasite, which the host?

Yeon-kyo tries her hand at housework

Parasitism is an apt metonym for Bong Joon Ho’s project. Even in its evolutionary sense, parasitism is positioned within a consumer-resource framework, well-fitted to a capitalist critique. The Kims, unable to attain work through typical channels (one might say foraging), use their cunning to gather resources in another way: a parasitic relationship, latching on to a bigger beast. In Parasite, the “normal” order of capitalism has been infiltrated by something nefarious. “I only trust someone recommended by someone I know well,” Yeon-kyo, the madame of the house, says imperiously. “The chain of recommendations is best.” Presumably, her previous tutor, Min, introduced another creature like himself: a well-off college student from a good family. But when Min unclasps that chain by bringing in Ki-woo, it is rebuilt link-by-link with another kind of organism. Central to the horror of Parasite is the possibility that the invisible, omnipresent keepers of the house — supposedly brought in by an infallible chain of recommendations — are not only not who you thought they were, but are actively conspiring against you. What you mistook to be one of your own is instead an alien organism — and it’s got you surrounded.

But the Kims aren’t the only parasites in need of new hosts to feed on. This year and last, the Oscars were quite literally host-less, in search of a new blood. It’s not a coincidence that this year — the lowest year of viewership since it’s been televised, and in trend with dropping numbers for a decade now — is the year the Academy Awards decided to grant its most prestigious award to a foreign film. The Oscars have been the target, for years, of condemnations of racial discrimination, most notably with the trending hashtag #OscarsSoWhite, but long before that as well. Marlon Brando refused the award in 1972 for the film industry’s discrimination against Native Americans. Incredibly, in its history, more White actresses have won Oscars for yellowface roles then actual Asian actresses.

Picture Credit: Walt Disney Television

William Friedkin, an Academy Award-winning director and former producer of the Oscars ceremony, described the Oscars as “the greatest promotion scheme that any industry ever devised for itself.” The nominees for Best Original Song often perform those songs live at the ceremony, and their performance is used to promote the television broadcast. Of the 5,100+ publicly-known members of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, which votes on nominations, 94% are Caucasian, 77% male, 54% over the age of sixty, and 33% are themselves former nominees and winners. (One can’t help but recall Park Dong-ik’s words — “the chain of recommendations is best.”) Absurdities abound: Oscar awards cannot be sold, except back to the Academy, and then only for $1. The Academy Awards TV broadcast holds the record for winning the most Emmys. The Oscars are parasitism incarnate, and it has been feeding on itself for years.

The Oscars are parasitism incarnate, and it has been feeding on itself for years.

While the endorsement from the Academy certainly bears cultural weight, Parasite was not a movie that needed the Oscars. More people might have been swayed to see the film after it swept the season — but it certainly had no shortage of fans beforehand, even in the West. (Not a big moviegoer, I saw the film long before the Oscars nominees even came out.) The Academy’s choice to elect Parasite was essentially a vote for itself: a safety-line for the survival of an industry indolent, self-indulgent, and frankly, dying. This isn’t to say that Oscar-goers didn’t love the movie — but the reason Parasite stirred such ferment is because, in an industry grown stilted, and centered around story-telling, Parasite’s win would introduce a fresh new storyline. Witness: the audience chanting “Up! Up! Up!” as the lights dimmed during the Parasite’s Best Picture speech. The time limit rule was originally introduced to eliminate what show organizer Bill Mechanic termed “the single most hated thing on the show”: long and embarrassing displays of emotion. But clearly the audience wanted sentiment now. Indeed, the Academy Awards audience, representatives of the movie industry, seemed almost to be engaged in an act of filmmaking as they clamored for lights—camera, action. Parasite’s win is a fairytale story indeed — with the role of the white knight clearly preordained.

It’s not that the Oscars don’t matter at all. Clearly, it’s still a source of pride. “And the winner is…a movie from South Korea!” pantomimed an indignant President Trump at a recent rally. “What the hell was that all about? We’ve got enough problems with South Korea over trade!” To a president with the soothsayer’s skill of seeing decline everywhere, America’s film industry is clearly another arena that needs to be made “great again.” And in their Best Picture speech, Miky Lee, the executive producer of Parasite, made clear how much their win meant to South Korea: “Without you, our Korean film audience, we are not here. Thank you very much.” No doubt Parasite swept because it came in at just the right cultural moment: class criticism is currently tearing through Korea at the same time that Bernie Sanders is storming through the US primary, that the UK prepares for Brexit, that countries around the world face some of the worst levels of income inequality to date.

But the power of Parasite is also in its incredible particularity. Though it may have succeeded in the Academy Awards because a Western audience can relate to its central themes, much in the film is also lost on it. A Korean audience, for instance, would likely get the joke when Ki-woo “directs” Ki-taek’s performance: Ki-taek clutching a script and gesticulating, Ki-woo telling him, “Cut, cut! Dad, your emotions are up to here,” (hand above his head) “Bring them down to about here” (lowering his hand). Song Kang Ho, the actor for Ki-taek, is one of Korea’s biggest stars, while Choi Woo Shik, who plays Ki-woo, is a newcomer – if anyone should be coaching, it’d be the other way around. And the presence of the scholar’s rock, which is introduced early and sets a mysterious theme throughout, would register to a Korean audience as a strange: families don’t typically gift each other scholar’s rocks. A Western audience, on the other hand, would likely Orientalize the rock as a normal part of the experience of Korean-ness — much like Harvey Weinstein so easily believed that Bong Joon Ho’s father was a provincial fisherman, rather than one of Korea’s most famed poets.

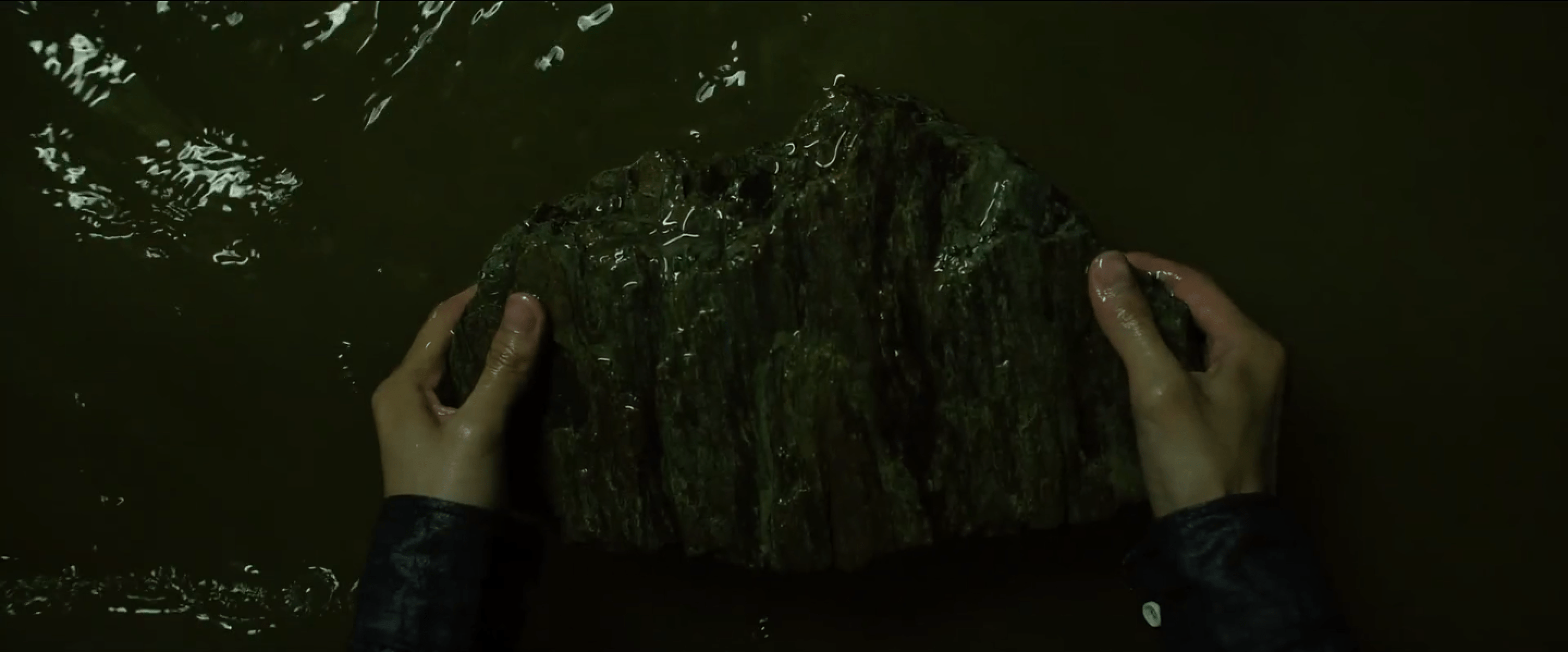

The scholar’s rock

“It’s so metaphorical,” gasps Ki-woo when Min presents him with the scholar’s rock. But if the rock is metaphorical, it’s the most mysterious fetish of the film. It seems to bring the Kims luck — but only sort of, and for a time, until their lives fall apart. In a much more real way, it’s Min, who has actual material means, that gives them their lucky break. When the Parks return to their sub-basement home in the middle of a flood, the scholar’s rock floats mysteriously upward to the surface into Ki-woo’s waiting hands. He seems to take it as a symbol, intending to deliver it to the basement-bound Geun-se, perhaps to bring good luck to his family as well. But in its most decisive role in the film, the “metaphorical” scholar’s rock is only a blunt-force object, used by Geun-se to bash in Ki-woo’s head. As if to underscore the point, after knocking Ki-woo out, he pauses, tilts his head, picks up the rock, and slams it down a second time. A rock, Parasite seems to suggest, is sometimes just a rock.

A rock, Parasite seems to suggest, is sometimes just a rock.

The other time Ki-woo proclaims “it’s so metaphorical!” is in reaction to Yeon-kyo’s showing him her son Da-song’s drawing. A true believer in his artistic talent, she’s totally unfazed when Ki-woo says, “It’s a chimpanzee, right?” She replies, dreamily, “A self-portrait.” If the scholar’s rock is but a blunt object, Da-song’s artwork is certainly a dud. (“Did you know Da-song is faking it all?” Da-hye demands of Ki-woo. “It’s all a show!”) But Yeon-kyo is an easy audience, and Ki-jung especially plays her to maximal effect. Clad in all black, adopting a look of half-lidded serenity, she elicits a sob-gasp from the madame with the shot-in-the-dark question “Did anything happen to Da-song in the first grade?” pointing to a made-up “schizophrenia corner” of his drawings. It is Ki-jung throughout who is both most resigned to the grim reality of their situation, and, possibly as a result, most adept and unrepentant about manipulating the Parks for personal gain. Art, and all the high-minded nonsense it brings along, Ki-jung seems to believe, is for rich people, and for suckers. Parasite is a class critique, rife with metaphor — but it’s also, quite simply, a tragedy about the ravaging of families.

Ki-woo and Yeon-kyo contemplate Da-song’s art

This subtle lambasting of a too-reverent reading of art and the systems that prop it up is central to Bong Joon Ho’s larger project of undermining the loci of power in the most blasé ways. Asked about his thoughts on the Academy Awards having nominated not one Korean film in its entire history, Bong shrugged, then offered a devastating condemnation. “It’s a little strange, but it’s not a big deal,” he said. “The Oscars are not an international film festival. They’re very local.” After receiving a dictatorial eight minutes of standing ovation at the prestigious Cannes film festival, the first South Korean film to win the Palme d’Or, and the first to win a unanimous vote in years, Bong came to the stage and delivered the following speech: “Thank you. Let’s all go home.” He explained later that he and the cast were all hungry because the screening was late at night and they hadn’t eaten dinner, recalling Chung-sook’s grumbling admonition, after the family fawns over Min’s scholar’s rock: “food would be better.” Indeed, the un-metaphorical scholar’s rock seems to have become a potent symbol outside of the film. Accepting the Oscar, Miky Lee utters nearly identical words to Ki-taek, as he first appraises the rock: “This is a very opportune gift.” A Korean film sweeping the Oscars is “so metaphorical” — or maybe Korea has been a powerhouse in cinema for at least two decades now, and the Academy simply chose the most opportune time to notice.