The Problem With “Fresh Start” Cities

By Cassidy Warner

Staff Writer

10/5/2022

The plan to relocate Indonesia’s capital from Jakarta to a completely different island in the archipelago by 2024 is an ambitious, problem-riddled project. Rather than moving to an existing city, the government intends to build an entirely new one, a clean slate that would supposedly not be plagued by the many issues (like natural disasters, terrible traffic, and lack of clean water infrastructure) that currently beset Jakarta.

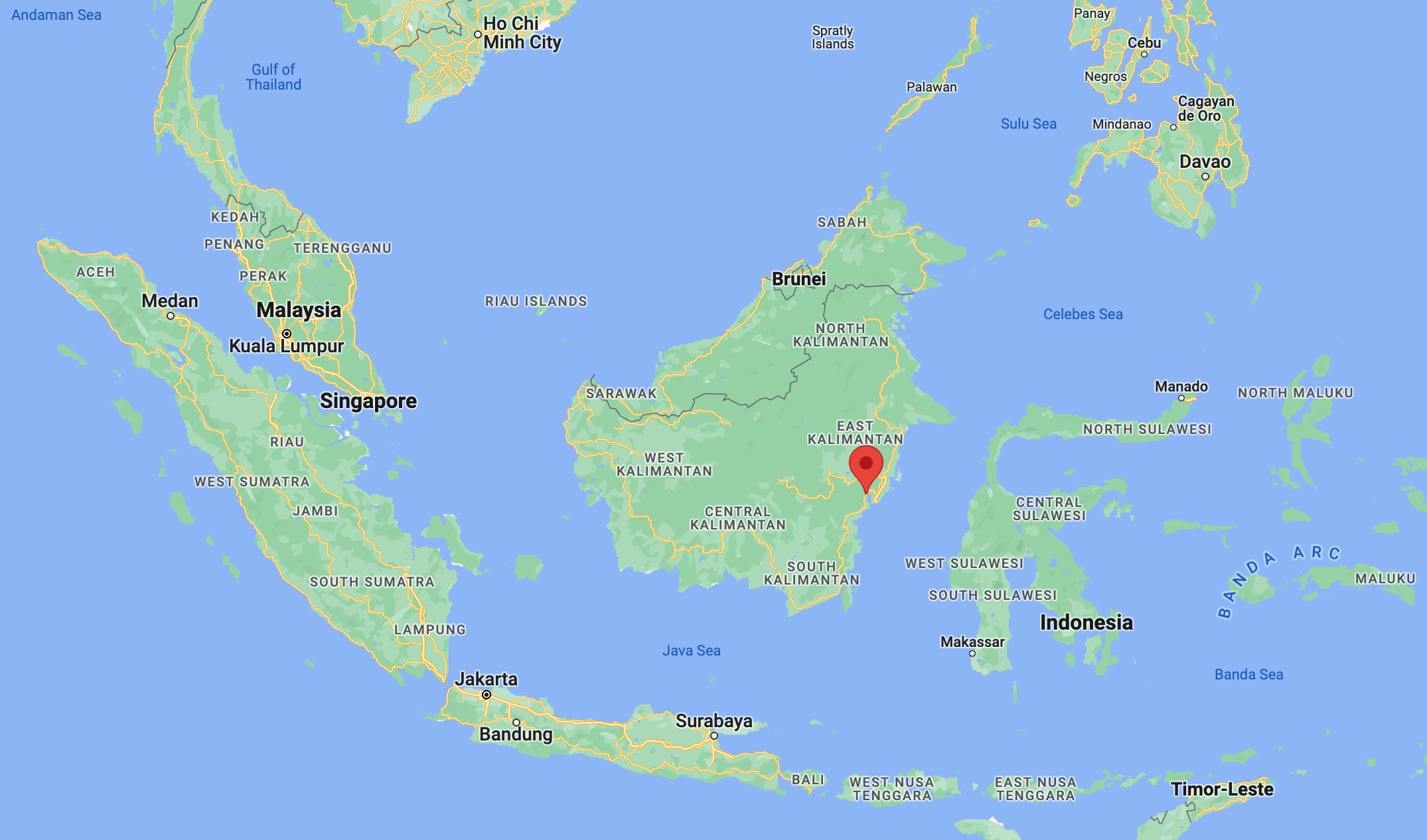

Map showing the location of Nusantara

But the new capital, Nusantara, will create problems of its own, including the impact of sudden, overwhelming urbanisation on the island’s virgin, protected ecosystems and the local indigenous population.

Currently, Jakarta is a sprawling, overcrowded, drowning city. It is also a primate city, 3-4 times bigger than any other Indonesian city. Looking at it from the air, BBC correspondent Gordon Buchanan described it as a “big sea of grey and brown…rapid urbanisation gone horribly, horribly wrong.” President Joko Widodo has stated that “the burden [on Jakarta] is too heavy as the centre of governance, business, finance, trade, and services.” Originally designed to accommodate only 800,000 people, Jakarta now houses 11 million and explosive overdevelopment, combined with necessary but unsustainable water consumption from the city’s underground aquifers, is quickly destroying the land upon which the city rests. With certain parts of the city sinking up to 25 cm per year, and sea levels rising another 0.43-0.53 cm, somewhere between 25%–33% of the city is expected to be underwater by 2050. The city is shrouded in smog and pollution, girded by poverty and slums, and is living on borrowed time before being eventually swallowed by the sea. Already, 40% of Jakarta is below sea level and there are coastal suburbs as deep as 2-3 meters below sea level, relying on cracked and leaky sea walls to keep them safe.

Jakarta

And none of these problems are getting better; most are getting worse.

Given these overwhelming, systemic problems, it is not surprising that the idea of a clean slate city appeals. Nusantara is supposed to be a fresh start, a chance to do better and address all of the issues that seem too hard to solve in Jakarta. As an added bonus, constructing the new capital will even help to ease congestion in Jakarta by removing the centre of governance, as well as an estimated 1.5 million of its residents by 2028.

But, however alluring the idea of a clean slate city is, these cities are rarely the panaceas or utopias their creators envisioned.

However alluring the idea of a clean slate city is, these cities are rarely the panaceas or utopias their creators envisioned.

Indonesia is not the first country to be seduced by the promise of a fresh start. Australia moved its capital in 1911 after creating Canberra, Brazil and Pakistan both moved their capitals to new cities (Brasília and Islamabad) in 1960, Nigeria built its new capital, Abuja, in the 1980s, and Myanmar moved its seat of government from Yangon to Nay Pyi Daw in 2005. Egypt is supposed to be moving its capital to the New Administrative Capital soon, after postponing the move in 2021 due to the pandemic. Similarly, Malaysia built Putrajaya to be the nation’s administrative capital in 1995, but kept Kuala Lumpur as its official capital.

And in addition to these brand-new capital cities, there have also been plenty of regular new cities, including Sejong and Songdo in South Korea, and Khorgas, Liuzhou Forest City, and Meixi Lake in China. Malaysia wants to open its own Forest City in 2035, Kazakhstan is building an economic oasis, Nurkent, near the border with China, Sri Lanka hopes to debut its Colombo Port City in 2041, and Egypt will add to Cairo and New Cairo with New New Cairo at an unspecified future date.

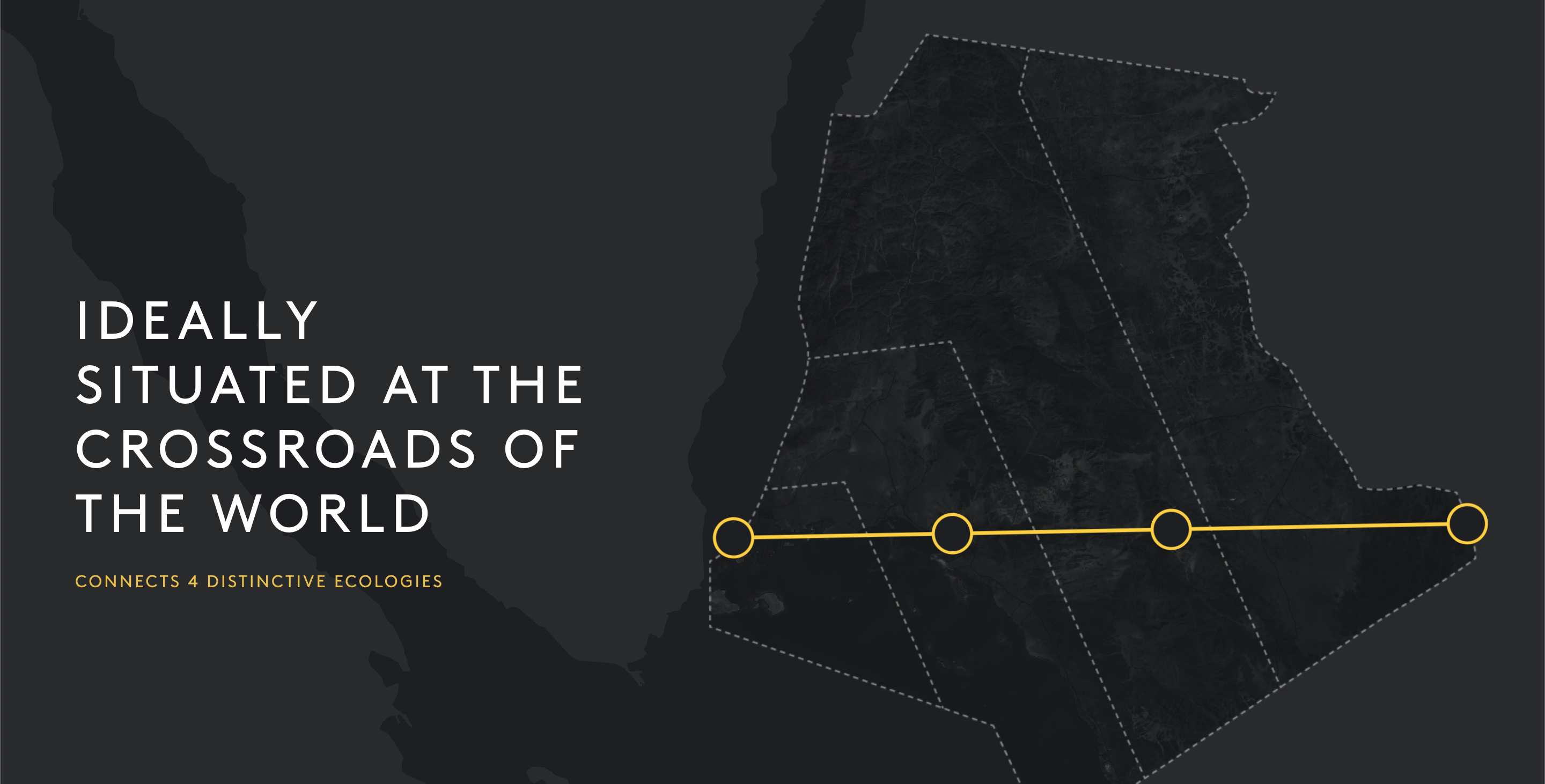

A common theme among these cities is sustainability, integration with the environment, and clean energy. The dream for Nusantara, for example, is to be “a new high-tech, smart city, surrounded by forest.” Futuristic renders show blue skies and lush green spaces, buildings surrounded by gardens, and crystal-clear waterways that weave through modern, architecturally interesting buildings. Similarly, The Line is depicted as a vivid green stripe cutting across Saudi Arabia. Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince, presented the project as “a city of a million residents…that preserves 95% of nature…with zero cars, zero streets, and zero carbon emissions.”

Screenshot from the website devoted to The Line

But dreams like these do not easily align with reality. For The Line, “preserving 95% of nature” is a remarkably optimistic take on miraculously spawning green spaces throughout inhospitable desert and mountainous terrain. For Nusantara, the problem is reversed: forest is currently abundant, but it is unclear how the Indonesian government will protect that forest coverage when the city centre inevitably expands to cope with the city’s increasing population. Planning Minister, Bambang Brodjonegro, optimistically promised that “we will not disturb any existing protected forest, instead we will rehabilitate it.” One of the problems with this promise is that only a small section of Borneo (the “Heart of Borneo”) is considered protected, meaning that all other forests would be fair game for logging and development. Initial development of Nusantara might remain mindful of its effect on the surrounding forests, but it is less likely that the city’s inevitable, unplanned expansion will do the same.

Additionally, green cities often fail to achieve their internal ecological targets. More often than not, new cities shoot for the stars – they want carbon neutrality, green energy generation, high public transport usage, reclaimed and recycled water usage, >50% green spaces, etc – but, ultimately, these planners are asking too much from a space that must still be fundamentally urban. For example, China’s Dongtan was supposed to be the first “eco-city,” a model of urban sustainability for the world; instead, the project reneged on most of its promises, failed to meet basic targets, and instead resorted to “greenwashing” (the construction equivalent of false advertising and virtue signalling). According to Li Xun, secretary of the Chinese Society for Urban Studies, only 20% of China’s eco-cities meet their ecological targets. The difficulty in achieving properly green cities is also exacerbated by issues with corruption: corrupt inspectors will sign off on subpar building materials and certify targets that haven’t been reached; corrupt officials will falsely claim to have met environmental targets to further their own careers; and government interference in science skews data and cripples third-party verification, because independent scientists fear retaliation for publishing reports that contradict government findings. Given that Indonesia is perceived to be even more corrupt than China, it is not unreasonable to expect even worse results with Nusantara.

But even if Nusantara does fulfill its green potential, there are other problems with new cities that make them unattractive places to live. Even though clean slate cities avoid mundane problems like traffic jams and overcrowding, they are nevertheless missing something crucial. In particular, they are often accused of being soulless, of missing that certain je ne sais quoi that makes cities interesting and engaging; and no amount of plant walls inside cafes and carefully sculpted parks can change that.

New cities are often accused of being soulless.

Canberra, for instance, was once described by England’s Prince Philip as having “tremendous advantages from an administrative point of view,” but ultimately lacking “soul;” he went on to say that the city was “miss[ing] a little something of the human cussedness which makes a town worth living in.” Similarly, when reviewing Malaysia’s Putrajaya, travel writer Brian Johnson conceded that despite its lack of traffic and its beautiful green spaces, the city “has its troubles luring people to live [t]here.” Malaysian journalist Adzhar Ibrahim, went further, saying he hates having to go to Putrajaya and despises it for its “blandness;” despite “the wide-open spaces” and “architecture meant to be majestic and awe-inspiring,” he finds the city “contrived, lifeless, and soulless.” Similarly, a top hotel review on Tripadvisor of Myanmar’s Nay Pyi Daw calls the city “a comfortable, soulless prison,” and goes on to say that only someone who requires “little social or psychological stimulus” could be happy living there.

Putrajaya

Brazil’s capital, Brasília, has attracted similar criticisms and has even been described as a “cautionary tale” for aspiring new city planners. The centre of the city, the “Pilot Plan” has indeed turned out very nearly as intended, and is currently a pleasant place to live, according to Jorge Guilherme de Magalhães Francisconi, a former architect and urban planner who has lived in Brasília since the 1970s. But the Pilot Plan only accommodates 300,000 people and Brasília now needs to house 2.5 million. Almost as soon as construction began, “temporary” worker camps sprung up and never disappeared, leading to a ring of slums that still surround the beautiful city centre. The Pilot Plan is “a little island, or cocoon,” said Vicente Del Rio, a Professor Emeritus of City and Regional Planning at California Polytechnic State University. Only a select few, wealthy and powerful, can afford to live inside the bubble, leaving everyone else out in the cold.

Pilot Plan, Brasília (Picture Credit: Arturdiasr)

Additionally, the “cocooning” effect cited by Del Rio can have more sinister consequences. According to Dr Petr Matous, an Associate Dean at the University of Sydney’s Faculty of Engineering, geographically isolated administrative cities like Nusantara lead to “measurably reduced political accountability, diminished provision of public goods [and] increased corruption.” Indonesia already suffers from high levels of corruption, with 92% of Indonesians believing that government corruption is a “big problem” and 30% of public service users having paid a bribe in the last year; and Nusantara’s inherent isolation runs the risk of creating an “ivory tower” where lawmakers and politicians are further cut off from ordinary Indonesians and their problems.

Nusantara’s inherent isolation runs the risk of creating an “ivory tower” where lawmakers and politicians are further cut off from ordinary Indonesians and their problems.

Australians are currently fighting a version of this problem. Australian news media regularly refer to the capital as the “Canberra bubble” and politicians themselves are accused of being “out of touch” at least once a week, and very often more. Rural Australians affected by climate disasters like flooding and bushfires are poorly served by wealthy politicians who are insulated from, and thus disinterested in, their struggles. For Indonesia, this point is particularly relevant as one of the main stated aims of moving the capital is to keep it safe from natural disasters. But the existence of Nusantara will not lessen the risks for everyday Jakartans; it will just make their problems easier to ignore.

Canberra (Picture Credit: Jason Tong)

Although Nusantara will face its own unique challenges, the city’s planners can still glean lessons from the cities that have come before it.

For example, all of these prior attempts at city planning seem to have forgotten that the primary beneficiaries are supposed to be its denizens. Brasília was a visionary, artistically designed collection of buildings that failed to consider the experiences and lives of the people who were supposed to live in it, especially the lower classes. It only took a decade for Brasília’s population to become twice as large as initially planned for; two decades later, the population had more than doubled again. If Nusantara hopes to preserve the precious forest around its city centre, and avoid unsanitary and unsustainable slums, it must plan for these people.

It’s also important to invest in real eco-friendly technologies from the beginning. For example, Nusantara should have clean energy infrastructure like solar or wind from the get-go, rather than relying on coal and intending to transition later. Rather than assuming that everyone will suddenly be happy to take public transport, it should arrange for cleaner versions of familiar modes of transport, like e-Taxis and electric cars (run off that pre-existing green energy grid). The city also needs to be self-sufficient, rather than relying on continual, carbon-costly imports that undermine the city’s green goals.

Nusantara has the potential to pilot a happier, healthier future for Indonesia – and to become a model for other countries. But if the Indonesian government loses sight of the people who are meant to benefit, then moving the capital will only exacerbate the country’s already existing problems like environmental degradation, corruption, and inequality. There’s no point in a fresh start if you’re just going to bring along your old baggage.