The Rule-Bender

By Shruti Kothari

Staff Writer

11/8/2020

Thanachat Tullayachat plays Sri Thanonchai in Srithanonchai 555+

One of the most popular folk heroes of the Ayutthaya Kingdom (1350-1767) was the Thai trickster Sri Thanonchai. Called Sieng Mieng in Laos, Ah Thonchuy Prach in Cambodia, and Saga Dausa in Myanmar, he became a household staple across Southeast Asia, and all accounts describe a man with a brilliant mind, but questionable morals. Like a lawyer, Sri Thanonchai is known for his creative interpretation of language, which enables him to wend his way around rules. The combination of highbrow wordplay and lowbrow humor in Sri Thanonchai stories continue to delight audiences to this day.

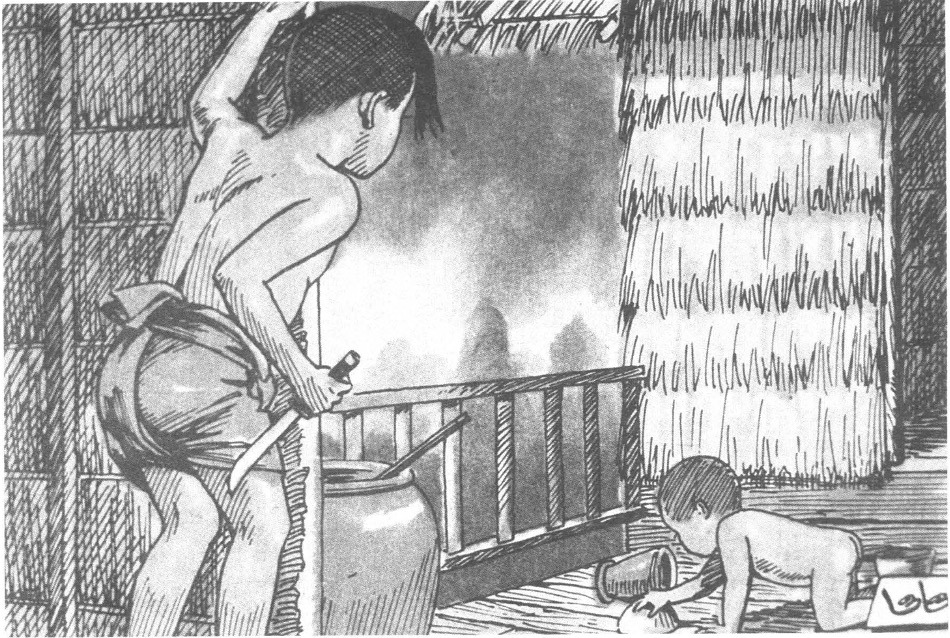

Born to peasants, Sri Thanonchai’s crafty and malevolent nature was apparent even from childhood. When his mother bears another son, he soon grows jealous of him. One day, when his mother is leaving the house for the market, she asks him to clean his younger brother “in and out.” Sri Thanonchai wilfully misinterprets these instructions, and “cleans” his brother as one would meat. He slices the baby open, belly first, removes his innards, and butchers him. When his parents find their youngest sliced and diced, ready to eat, they finally realize that a Brahman prophecy that their eldest would be exceedingly clever is not the blessing they thought it would be. Horrified, they send Sri Thanonchai away to a temple to be raised by monks.

That first episode is only the beginning of the troubles the trickster brings to those around him. He makes no friends as a young monk, as he is constantly throwing his fellow novices under the bus to cover up for his laziness and misdeeds. Perhaps the most famous example of this is when the roof of the temple begins to leak and fall apart. The novices are tasked with repairing the roof, which they do, while Sri Thanonchai opts to relax instead. When the novices complain to their teacher, Sri Thanonchai decides to save his hide by spending all night re-fixing the roof in the exact opposite way. In the morning, the teacher begins to scold Sri Thanonchai. However, he interrupts and asks his peers to describe the roof as it stands; when their answers obviously no longer match the reality of the repairs, the teacher is convinced that the other novices were lying, and that Sri Thanonchai singlehandedly completed the task.

In most versions, Sri Thanonchai never makes it as a monk: he’s defrocked well before then. He works for a sweets merchant for some time, who orders the trickster to never come back in the evenings with any merchandise left in hand. In true Sri Thanonchai fashion, he throws the sweets into the river on the way back. Understandably, his boss fires him. He works for another merchant who asks him to tie up his cattle. Sri Thanonchai obediently ties ropes around the necks of the unfortunate bovines and hangs them from palm trees. When the merchant returns home to find his dead cattle swaying in the wind, he decides to fire Sri Thanonchai, too.

Not even the elderly are spared. In one story, he borrows money from an old woman and says he will repay it after two moons. Two months later, the woman asks for her cash back, and the trickster explains to her that he has yet to see two moons at once. Eventually, Sri Thanonchai himself is tricked and forced to cough up when a novice monk comes to the old woman’s aid and shows the trickster a full moon in the sky reflected in water, thus two moons at once.

Is “trickster” too kind a label for Sri Thanonchai? After all, the fact that he was willing to cheat a poor geriatric (and commit fratricide and bovicide) ought to put him in the realm of villainy. However, some of his other exploits are less malevolent, and some even end up benefiting the country.

Is “trickster” too kind a label for Sri Thanonchai?

One day, Sri Thanonchai is introduced to King Jessada, who appreciates his quick wit, and their friendship and intellectual rivalry form the basis of a series of popular stories. Visiting foreign dignitaries frequently present the king with challenges, and the king becomes dependent on Sri Thanonchai to face them. One visitor brings his prize bull to court and declares that nobody can beat him in a bullfight. Sri Thanonchai, champion of Team Thailand, brings a calf to the ring. The bull apparently refuses to fight a child of its own species, and Thailand gains face.

Perhaps what makes Sri Thanonchai so popular in Thailand, a perennially hierarchical and non-confrontational society, is his ability to exploit loopholes to gain the upper hand. His antiestablishmentarianism delights the downtrodden, and while he constantly bends the rules, he never, ever breaks them.

His antiestablishmentarianism delights the downtrodden, and while he constantly bends the rules, he never, ever breaks them.

In one episode, Sri Thanonchai goes to China, where commoners are not allowed to gaze upon the king’s face. He dislikes this law, but doesn’t rail against it. Instead, he tells the king he will show him how to eat a convolvulus tied to the end of a string. Fascinated, the king watches. Sri Thanonchai contorts himself to eat the hanging flower, such that he is able to look at the king’s face directly. When the courtiers notice his crime, Sri Thanonchai successfully argues that it was the king who looked at him, and not the other way round. In another account, the Thai King Jessada wants to reward Sri Thanonchai’s cleverness, and asks him how much land he would like. Sri Thanonchai replies, “enough for a cat to die in.” He proceeds to chase a cat around and whip it, prompting it to run. By the time it it dies of exhaustion, it has traversed a large tract of land, which he claims for his own. In the context of Thai graeng jai culture, where one feels embarrassed or ashamed to speak up or ask for much, this solution is brilliant to listeners.

Another reason for Sri Thanonchai’s popularity are his comedic interactions with the king. Once, Sri Thanonchai serves the king a vessel in which he says he has captured the most exquisite scent in the world; the king inhales deeply and finds, to his shock, that the courtier has served him a fart in a pot. On another occasion, Sri Thanonchai gives the king special white chalk. When it won’t write, the trickster tells the king to wet the tip with his tongue. When the king puts it to his mouth, he realizes that he’s been given a stick of vulture shit. Another time, the king’s wife is terribly sick, and he calls Sri Thanonchai for his counsel. Sri Thanonchai solemnly declares that the queen will die in seven days. He later explains that he meant she will certainly die on one of the seven days of the week. The king is beloved for (largely) remaining sporting in the face of Sri Thanonchai’s morbid antics; in fact, he frequently pranks the trickster back.

When Sri Thanonchai dies (stories differ on his exact cause of death, but they all boil down to heartbreak at being outwitted), the king decides to have the last laugh. As the body is being cremated, the king asks his concubine to urinate on the bones. However, Sri Thanonchai wins – he asked his own wife to ensure the wood used in his pyre was a type that caused irritation and illness when burned, and all present, including the king, suffer greatly from this last trick from beyond the grave.

Today, Sri Thanonchai’s adventures are detailed in murals across the walls of the temple Wat Pathum Wanaram Rajaworawihan. Colloquially, “Sri Thanonchai science” or a “Sri Thanonchai solution” describe tricksy ways to deal with problems. The Economist described the 1997 Thai Constitution as being written to “foil latter-day Sri Thanonchais,” as in, to leave little room for interpretation. He features in children’s bedtime stories and school lessons, comics, and movies – the most recent being a 2014 comedy called Srithanonchai 555+ (the number 5 denotes “ha” in Thai).

Politically, however, the character of Sri Thanonchai has fallen from grace. Politicians and officials no longer speak of him as someone who overcomes oppressive power structures. Instead, he’s depicted as someone who misuses the power of his intellect for personal gain. In September 2019, Sanik Aksornkoae, the chairman of the National Economic and Social Development Council, said in an interview, “We men should not act like Sri Thanonchai, my father always taught and instilled. Those people, particularly with wit and intelligence, should try to behave the most and do only good things, otherwise they will cause collateral damage to the society, community, or even country they live in.” A 2007 art exhibition called “The Art of Corruption” prominently featured the trickster, alongside portrayals of Thailand’s notorious ex-Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who had just fled the country and was accused of corruption. Last December, reporters gave unflattering nicknames to major politicians, including “Rat Poison,” “The Undertaker at the Top,” and “The Demolisher.” The nickname of Deputy Prime Minister Wissanu Krea-ngam? “Sri Thanonchai.” Celebrated or villified, hero or villain, the last thing Sri Thanonchai is, though, is irrelevant.