Who Will Inherit the Earth? Who Cares?

By Cassidy Warner

Staff Writer

14/9/2021

Picture Credit: keso s

I don’t intend to have kids. I used to think this was an apolitical, personal choice: most kids are cute but annoying, and the rest are ugly and annoying. People usually assume that I will change my mind – after all, that biological clock is counting down the hours until my hormones drag me into a back alley and beat all rational thought from my mind.

But I am not alone. All over the world, fertility rates are falling. More and more women are surviving the hormonal assault and reaching the same conclusions; having babies just isn’t worth it, whatever “it” is.

When women reach these conclusions, they are thinking of babies not as demographic assets, but as personal burdens: difficulty re-entering the work force, longer hours of domestic labor, less sleep, altered bodies and relationships. And the more children they have, the larger the burden. Raising a child takes precious time and energy, which is why so many women today are opting out of it.

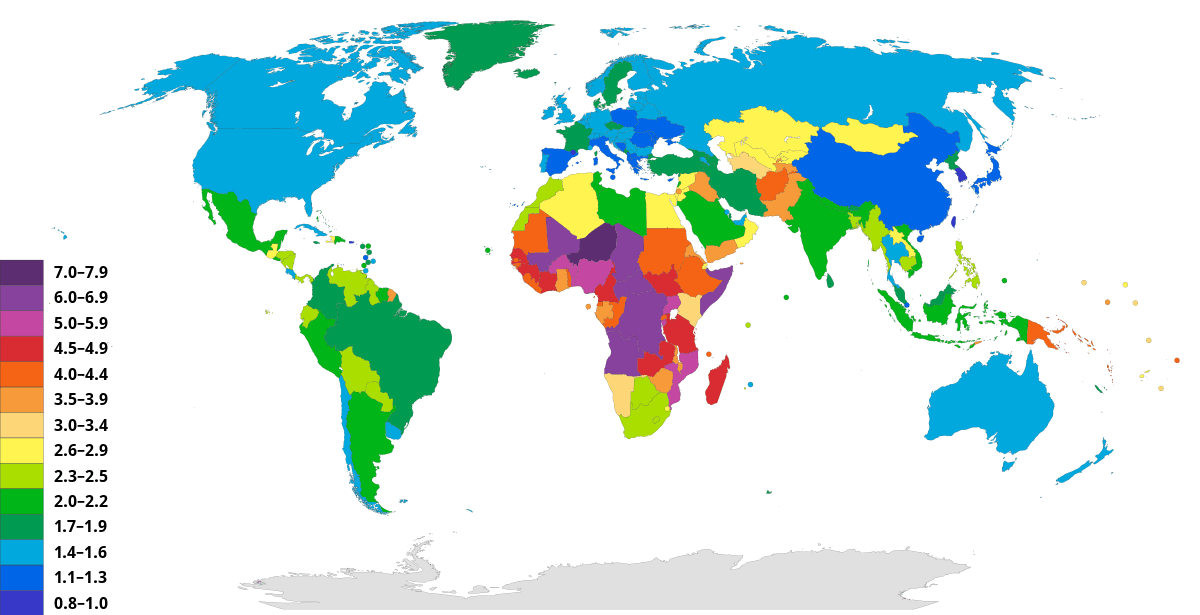

But these “personal choices” have national and global consequences. Take South Korea, which has the lowest fertility rate in the world at 0.92 births per woman. To maintain a static population, a country’s fertility rate needs to exceed 2.1, which means that South Korean women are currently having less than half the number of babies needed to maintain the current population. Similarly, Japan’s fertility rate is only 1.4 and the country’s population is expected to decline by 16.3% by 2050.

Fertility rates by country (Picture Credit: Korakys)

The effects of these low fertility rates are severe and long-lasting, most notably in the way they interact with the global, capitalist economy. Capitalism requires perpetual growth, or at the very least, a stable workforce. A country beset by low birth rates has only one option to meet this demand: import workers to flesh out the thinning ranks of the labor pool.

A country beset by low birth rates has only one option: import workers to flesh out the thinning ranks of the labor pool.

It’s clear that children are a matter of national importance, as evidenced by the “Do It For Denmark” campaign and China’s increasingly desperate attempts to promote fertility, raising the number of children couples are allowed to have from one to two in 2016, and again from two to three this year, and cracking down on tutoring to encourage parents to have more children. In a 2019 speech, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban even promised to exempt women who have four or more children from income tax for the rest of their lives.

But if immigrants are ready and willing to prop up your declining population, why spurn them and instead try to bribe your country’s women to have babies that they don’t want?

The answer is politics – specifically, identity politics. In that same speech, Orban declared, “we do not need numbers. We need Hungarian children!” Similarly, despite its stagnant economy (so bad, in fact, that economists call its last 30 years “the lost decades”), Japan has allowed few migrants into the country, and its immigrant population is only 2%.

Witness, also, the anti-immigrant sentiment that Trump tapped into in 2016. Scholars like Isabel Wilkerson have suggested that Trump’s victory was a result of population projections predicting that whites would be a minority in the United States by 2045. According to the US Census Bureau, already less than half the children in the US are non-Hispanic white (49.8% of under 18s in 2020) and this figure will only increase as immigrant women continue to have more children than those born in the US.

So, no, the decision of whether or not to have children is not apolitical. The changing demographics of wealthy, developed nations and the resultant rise of populist political parties is proof that we care, deeply, about who will inherit our countries. An early example of this was the White Australia Policy. One of the first acts of parliament after federation in 1901, was to unequivocally prohibit all “alien colored immigration” and also to “reduce or deport” the number of aliens already in the country. These policies remained in force until the 1970s and were not about jobs or opportunities; they were about ensuring the succession.

The changing demographics of wealthy, developed nations and the resultant rise of populism is proof that we care, deeply, about who will inherit our countries.

But this sort of nationalistic (not to say racist) fervor falls flat with educated, and, on the whole, happy women who are too busy enjoying their freedoms; freedoms that will be curtailed as soon as a baby is thrown into the mix. Once upon a time, motherhood was considered a woman’s most important role in society, but a recent survey of Australian women found that 74% no longer thought that children were necessary for a fulfilling life. In fact, in 2019, Peter Dolan, a professor of behavioral science at the London School of Economics found that “the healthiest and happiest population subgroup are women who never married or had children.”

How can nations reconcile these competing desires? What policies could convince women to forfeit their personal goals for national ideals?

One option is to revoke women’s freedoms – specifically education and access to jobs. According to the Australian Institute for Family Studies, irrespective of a desire for children, less-educated women are more likely to have them. Similarly, women who work full-time are less likely to have children; or, if they do, to have less children than they want. Restrict a woman’s education and ability to work and she will not know better, or have anything better to do, than raise children. There is a marked relationship between the Gender Inequality Index (GII) and a country’s birth rate (the GII measures things like maternal mortality, women’s access to secondary education, labor force participation, and share of government – all obvious markers of freedom, or lack thereof). However, it’s difficult to imagine a future in which women in the Western world are forced back into the role of broodmares; militant feminists are on guard for exactly that dystopian future.

But if going back is not an option, what would count as moving forwards?

I can think of only one other way: baby-making à la Brave New World, an option that seems as unlikely as rolling back the feminist tide. Even if full responsibility for creating and raising children could be devolved upon the state, releasing women (and men) from the burden of maintaining the population, there would still be myriad practical and ethical concerns around the implementation of such a system.

Far from these extremes, in all likelihood, many women in developed countries will respond to this debate with a dainty shrug, and will carry on enjoying their freedom and independence, unconcerned with the baby-shaped holes they’re leaving in the fabric of society.

This is not an abandonment of nationalism so much as a realization of the individualism that men have long enjoyed. Fortunately, population maintenance no longer needs to be vertical between generations; immigration means it can be lateral, encompassing the world. The combination of declining birth rates in developed countries and increasing immigration to them have created a new cycle of life that ends not with renewal, but replacement.

And, if you happen to be part of a declining population, there is no personal reason to resist this trend. After all, it may be the people having babies who will inherit the earth, but it is the people who are not who are enjoying it now.