Modi and His Supporters Face a COVID Reckoning

By Asavari Singh

Contributor

13/5/2021

Ashok Amrohi had an advantage over most other COVID patients in India. The former ambassador to Algeria, Brunei, and Mozambique had connections in high places and no dearth of resources. Most crucially, he had been assured a bed at a top private hospital near New Delhi as part of a health scheme for retired diplomats. Yet, on the sweltering night of 27 April, none of this mattered. Amrohi died in car in the hospital’s parking lot, after waiting for admission for five hours. His death was later described as “shocking” by India’s foreign minister S. Jaishankar. Another diplomat wrote a piece accusing the hospital of committing “second degree murder.” News channels interviewed his tearful wife, who described how the hospital callously told her they could not help Amrohi until their “process” was complete. In social media conversations, there was incredulity and fear. Not about how something like this could happen, but about how it could happen at a reputed private hospital, and to someone like him.

Amid a devastating COVID wave in India, the protective, rose-tinted shield of privilege is finally cracking. Unlike the first wave last year, which primarily affected the urban poor, this surge has hit affluent sections of society hard: the corporate executives, software engineers, business owners, who generally lead sheltered lives in walled enclaves and apartment complexes. For the first time, they are experiencing what life is often like for the poor. They too have had to rely on the benevolence of strangers and the resourcefulness of profiteers. Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp have been buzzing constantly with appeals for help – do you have a contact for oxygen concentrators? Does anyone know any remdesivir suppliers? COVID scams and black markets have sprouted like mushrooms. The afflicted are still trying their luck with these, in the hope that their dealers are scrupulous enough to peddle authentic wares.

For more than two weeks now, India has recorded well over 300,000 COVID cases and 3,000 deaths every day. These, of course, are just the official figures –the endless mass cremations and the shortage of firewood in some cities indicate that the actual toll is likely to be much higher. More frightening than the pernicious new variants of the virus has been the yawning gaps in healthcare and the stalling of a much-vaunted vaccination program. Oxygen plants and supply chains that the government was supposed to have set up, are nowhere to be seen. As a result, even the best private hospitals have faced acute oxygen shortages for weeks. On 1 May, 12 people died in a posh Delhi hospital when it ran out of oxygen, and similar incidents were reported in Bangalore, Gurgaon, and Jaipur. Prescriptions are difficult to fill because pharmacies have been running out of drugs. There are vaccine shortages at a time when only about 2% of the population has been fully vaccinated. People wait in long queues at hospitals, and bodies wait in long queues at overburdened cremation grounds.

A man with oxygen cylinders in India

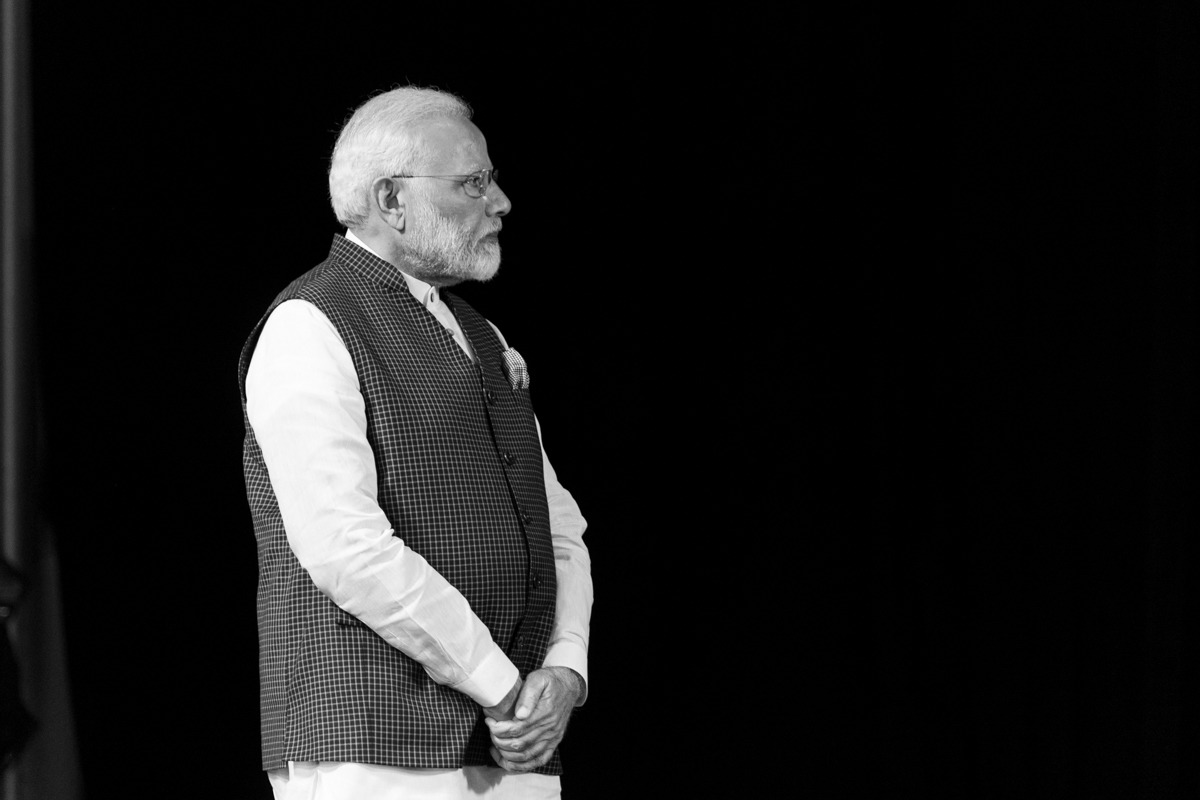

In this unprecedented situation, even diehard supporters of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) are questioning the reality vs. collective fantasy of India, the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and the promise of incipient superpower status for India that he represented.

Even diehard supporters of the BJP are questioning the reality vs. collective fantasy of India, and the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

In 2019, Modi won a second term with a thumping majority. People from across social strata put their faith in him, but it was wealthy urban-dwellers who were the most emphatic – 44% of them voted for BJP, his political party, followed by 36% of the lower classes. All categories of supporters were satisfied for the most part. The Hindu hardliners were promised the construction of a major temple and this was delivered promptly. The poor, known for their fatalism and low expectations, were easily satisfied with populist measures like free gas cylinders. The really big promises, though, were designed to appeal to the urban aspirational class and also to influential Indian communities abroad.

Sudie Sengupta, a management consultant, had been working in New York when Modi came into power in 2014 and then again in 2019. According to him, Modi inspired self-belief in Indians who struggled with feelings of inferiority due to their “third world tag.” Like many other upper-class Indians, Sengupta made his peace with the government’s religiously divisive agenda although he never agreed with it. “India for a very long time has needed a leader who could stand up and speak up,” he said. “Modi filled that vacuum. He didn’t just express hopes for India, he showed resolve. He went around the world and engaged with China and the US as an equal, no matter that he spoke in broken English.”

Even when things did go south from time to time, Modi’s supporters were quick to praise his decisiveness and to forgive flaws in his planning and execution, like during the hugely disruptive (and pointless) demonetization of high-currency notes in 2016 as a measure to fight “black money.” He was nicknamed the “teflon” prime minister because criticism never seemed to stick to him. In March 2020, when he abruptly imposed the “world’s strictest coronavirus lockdown” for two months, they felt his intentions were good even if his measures pushed 230 million Indians below the poverty line and cost the middle and upper classes significant income losses. When India’s GDP shrank by a record 23.9% in the first quarter of 2021, it was accepted that this collective suffering had to be undertaken to save India from COVID. Many of the wealthy took to repeating Modi’s refrain whenever the economic impact of the lockdown on the desperately poor was mentioned: “There can be wealth only if there is health.” They could overlook the fact that while many migrant laborers died or fell sick as they tried to walk back to their villages, rich Indians “stranded” abroad were brought home on special flights. There was the general consensus that a few people may have starved to death, but that Modi had saved millions of lives. Not just that, India, as the world’s biggest producer of vaccines, was billed as the global pharmacy and as a “vaccine superpower” that would rescue countries struggling with the pandemic.

Early this year, Modi bragged that India had “defeated” COVID. In his video address to the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Davos summit on 28 January, he announced that India had “not only solved our problems but also helped the world fight the pandemic” by exporting medicines to 150 countries and launching the “world’s biggest vaccination program.” He spoke eloquently in Hindi of his vision for a “self-reliant India” and how global supply chains would benefit as a result. Klaus Schwab, the founder and executive chairman of the WEF also praised Modi’s “decisive leadership” under which India demonstrated “extraordinary strength and resilience.” It was a moment of pride for many Indians – their country’s chance to demonstrate its soft power, and also to thumb its nose at those who predicted that India would get majorly pummeled by COVID. Newspaper editorials spoke triumphantly of “global wonderment” at how India performed better than the US, attributing the apparent success in overcoming the first wave to several factors: youthful demographics, Indians’ robustness due to exposure to all kinds of nasty germs, excellent governance, the nationwide lockdown, the public health messaging, the discipline of the 1.3 billion-strong population. “[L]ike it almost always happens, India and its people sorted things out,” wrote a prominent journalist in February.

It was around this time that COVID cases in India started creeping up steadily, and a small section of the media and scientists expressed fears that a second wave might be around the corner. No one paid much attention, least of all the government. Public transport, malls, and movie theatres continued to open up, and it was announced that a grand Hindu festival, the Kumbh Mela, would take place from 1 to 30 April on the banks of the holy river Ganges. Millions of devotees were expected to attend amid “strict COVID protocols;” the chief minister of the state further allayed fears by saying that the river’s blessings and the people’s faith would keep the virus at bay. On 27 March, in the eastern state of Bengal, month-long elections kicked off with fevered campaigning and mass rallies.

Crowds at the Ganges during Kumbh Mela

By mid-April, India was watching two sets of contrasting images. One was festive: hordes of bare-chested dreadlocked seers thronging to bathe in the Ganges at the Kumbh Mela, and crowded rallies in Bengal (where masks were few and far between) that were addressed by the Modi himself. The other set of images was frightening: hospitals with “no beds available” posters stuck outside, rows of bodies lined up to be cremated in makeshift funeral grounds, COVID patients gasping for breath on the streets.

The headiness of the previous months gave way to despair and rage. Modi had ensured that he was the face of India’s COVID success, but now this backfired and he just as easily became the face of its failure.

Modi had ensured that he was the face of India’s COVID success, but now this backfired and he just as easily became the face of its failure.

The BJP’s right-leaning urban supporters, many for the first time, spoke out against the leader who they had earlier thought could do no wrong. Even people who work for the party expressed outrage that the federal and (some) state governments were less interested in solving the crisis than in salvaging their image. They were, for instance, furious when a BJP chief minister directed officials to “take action” against those who and tried to “tarnish” the government’s reputation by talking about the lack of medical care. When Modi addressed the nation on TV, he offered no answers and, for a change, impressed no one. Hashtags critical of the government, like #ResignModi, #NoMoreModi, and #SuperSpreaderModi, trended for days on social media. When Twitter removed some tweets at the behest of the government, and when Facebook mysteriously blocked #ResignModi posts, the angry voices got louder rather than dying down. There was a further outcry when the federal government classified as “essential” construction work on the approximately $2.7 billion Central Vista Redevelopment Project – involving, among other things, a new parliament building and a palatial prime ministerial residence. It was lost on no one that the same money could have been used to build several new hospitals, or to create a welfare fund, or to procure more vaccines.

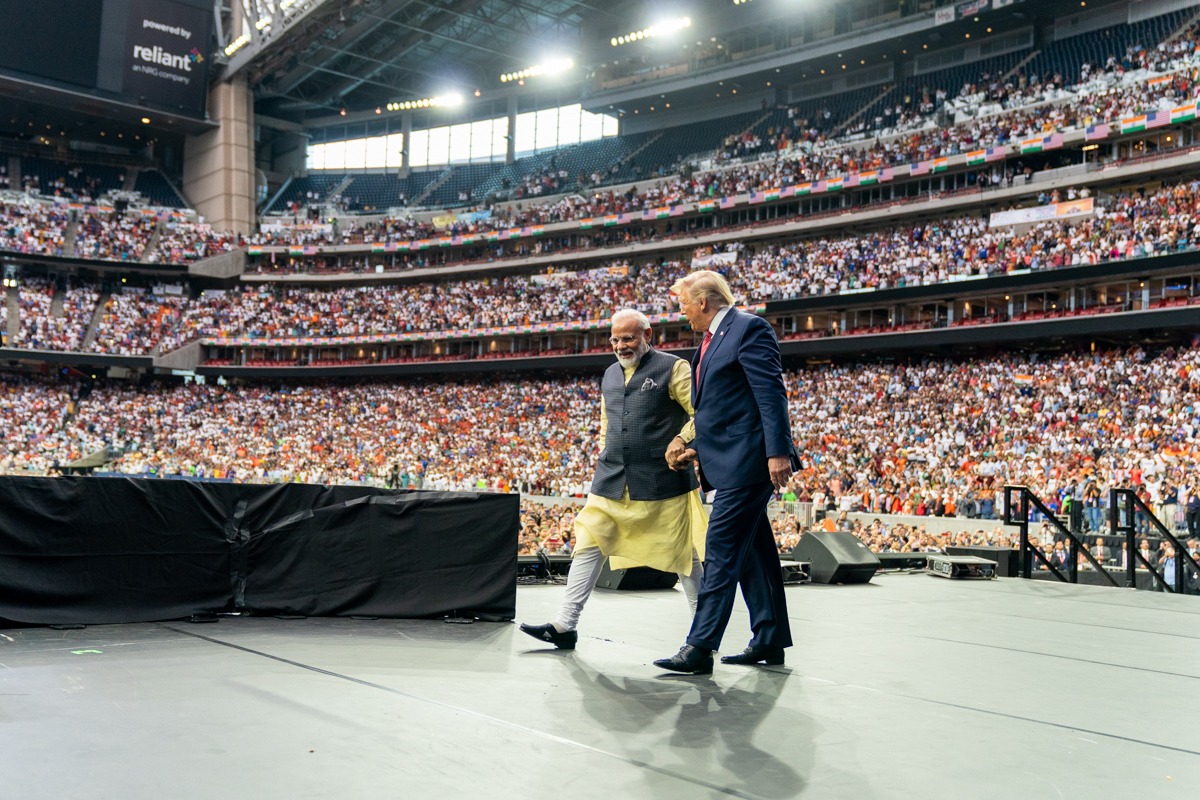

Even the government’s wealthy diasporic supporters were aghast at the headlines about the many preventable deaths and the harrowing updates they received from their friends and relatives in India. These overseas Indian communities had played a huge role in promoting Modi abroad and in helping to whitewash his reputation as a communally divisive figure. They had organized extravaganzas like “Howdy, Modi” in 2019, when Modi and former US President Donald Trump jointly addressed tens of thousands of people in Houston, and ensured that Modi got a “rock star reception” at Wembley Stadium in London. Modi had awakened their hopes about their country of origin but now he was being accused of being at the forefront of a “COVID apocalypse.”

Modi with Trump at the “Howdy, Modi” event in Houston in 2019

“We can justify a lot of things,” said a retired executive and former Modi supporter who did not wish to be named for fear of reprisal, “but when you start losing your loved ones due to the government’s negligence, you start asking whether you were wrong all along.” Many others are also suffering from a sense of shame, a wounding of national pride. For the first time in 16 years, India had to set aside its policy of not asking for foreign aid. Modi had gone on ad nauseum for months about his plans for a “self-reliant India,” and now India was forced to accept donations from the US, Taiwan, Japan, and others, although it stayed firm on purchasing rather than accepting gifts of supplies from regional rival China. “There’s a feeling of being defeated. We are looking bad in front of the whole world,” said Sengupta, who has lost loved ones to COVID. “It’s obvious now that the government has been focusing on winning elections and not on governance.”

“We can justify a lot of things, but when you start losing your loved ones due to the government’s negligence, you start asking whether you were wrong all along.”

Amit Sharma, an editorial photographer, said he started growing disillusioned with the Modi government a few years ago, but now he is feeling hopeless. “When I voted for them, they spoke the language of accountability, they reached out to people. But obviously it’s just like a TV show, one-way communication. There was so much talk of having beaten COVID but they didn’t prepare at all. They don’t even know how to distribute the aid we are getting. A lot of it is getting stuck.” Yet, despite his own anger, Sharma said focusing criticism on Modi merely plays into futile personality politics. “That’s a trap that the media and ordinary people are falling into. The government wants there to be battles between Modi-haters and Modi-lovers. It only causes more polarization, which ends up working in the government’s favor. People still aren’t asking enough of the real questions about why the hospitals aren’t functional or why there are no vaccines. No one can deny that those questions matter to everyone, but still we make it all about whether Modi is good or bad, what he is doing or not doing.”

Sharma acknowledges that the fact that questions are being asked at all, including by some who once blindly supported the government, is an encouraging sign. “If there is one silver lining to COVID, it is this. People are now seeing that all the talk did not translate to action. I feel awful about it.” He fears, though, that public memory is short. “They will spin new stories and people will forget what happened…in any case who else will they vote for? In their heart of hearts, they still believe that Modi will save them.”

Overall, the privileged urban classes do want to give the government another chance because they do not see a viable alternative in the opposition, and believe there are benefits to the multi-stranded ideological movement that the BJP has spearheaded since 2014. Many of them still hope that some sort of course correction is possible, and that the government will listen to them. They want redemption for Modi, even if it requires some intellectual contortions. “India is not a banana republic, and Modi is not like Xi Jinping or Putin,” said the retired executive who was quoted earlier. “Even now, Modi has to be given some credit for his foreign policy. India helped other countries, and so they were willing to help us in our time of need.” Jigar Shirish Dharamshi, a digital strategist currently based in Singapore, says he divides the Modi government’s performance into the pre-COVID and COVID eras. “I am extremely disappointed in the handling of this situation and the lack of empathy shown to the people, but to write Modi off now would be giving in to the recency bias. We need a leader who can take big and bold measures and he is still our best bet for economic and infrastructure development. Let’s remember that while the central government must take major ownership for what is happening, the people also slipped up and were not careful, and many state governments failed at their level too.”

Old patterns, ultimately, are hard to break and Modi’s government, for all its failures, continues to fill deep-seated emotional needs in the rich, urban voter base.

In his book The Gated Republic, journalist and author Shankkar Aiyar described how Indian citizens have “internalized the incapacity of the state to deliver public goods and services” and that millions are turning to private service providers and “opting out of holding governments accountable.” For the upper and upper-middle classes, especially, this system has become normalized. The main utility of the government to them is to feed the nationalist ego, stoke Hindu pride, raise the country’s status internationally, and fend off external threats like Pakistan and China. Thus, shows of “strength” rather than steady progress have become the metric of good leadership. It is generally taken for granted that those who can should fend for themselves on matters like health and education.

The privileged classes, true to type, are now turning even more inwards and devising their own solutions in the name of “self-reliance,” having perhaps realized that this was what Modi meant by the term all along. Swanky apartment complexes are setting up their own oxygen banks and scrambling to transform their clubs into residents-only healthcare centres. Some housing societies have imposed mini lockdowns with rules far more severe than anything currently mandated by the government. “Let’s remember we cannot outsource self-discipline to Modi,” said Sengupta.

Slums of Mumbai

The government, meanwhile, is rolling out “positivity” propaganda and trumpeting its push to set up oxygen plants and to provide vaccinations to all adults (even if booking an appointment on the central website has so far been nearly impossible). Already there are messages doing the rounds on WhatsApp groups about how we should appreciate what we have and “stop spreading negativity even if it is true.”

Yet, India’s COVID disaster has only just begun. Only about 30% of India’s population lives in urban areas, and the “quick actions” being taken by the government do very little for the villages and small towns where health facilities barely exist and there is an acute shortage of doctors and other medical personnel. The people here have no “private option” to turn to, no mini-republics to which they can retreat. There are already reports that COVID is ravaging rural India and villagers are starting to drop “like flies,” although reliable numbers are hard to come by in the absence of widespread testing and monitoring. Dozens of bodies, suspected to be those of COVID patients, have been found floating in the river Ganges, perhaps abandoned by frightened relatives.

As usual, the Indian government’s measures have been largely cosmetic and designed to appeal to the elites. The apps and online portals for vaccinations and oxygen delivery that the government is launching with much fanfare help the educated upper classes (to some extent), but they are inaccessible to the illiterate poor and village dwellers. For too long, the toiling masses of India have been expected to accept suffering as their lot, assuaged now and then by patchy welfare schemes and the opiate of religion. If this crisis should have shown the elite anything, though, it’s that, with COVID, at least, if they ignore the plight of the poor, they will soon share in their fate.

Related posts:

India Is Emulating China’s Worst Traits

Honest COVID Wedding Invitation

Tablighi Superspreaders in Pakistan

The Culture Factor in COVID-19

The Moral Foundations of Anti-Lockdown Anger

Are Anti-Lockdown Protests Legal?

Allegory in the Time of Coronavirus

Your Odds of Dying From COVID-19 Depend on How Polluted Your Air Is

Japanese Culture Isn’t Designed to Handle a Pandemic

The Coronavirus and the Crisis of Responsibility

To See How Coronavirus Outbreak might Play Out, Look at This Virtual Plague

FAKE NEWS | Nothing to Worry About, Says Wuhan Official From Inside Biohazard Suit